Chosen by Brian Short, President of the Sussex Record Society, text by Ruth Brown

The Sussex Record Society decided that the school log book of Thomas Slatford was so good it should be published, and so proceeded to do so this year! All headteachers of Victorian elementary schools were required to keep logs of their pupils’ progress, but few are as vivid and meticulous as this one. Head of Littlehampton Boys’ School from 1871 to 1911, he describes daily events in the lives of pupils, parents and teachers, along with his unceasing battles to overcome the inadequacy of his buildings and to get his pupils to attend regularly: Sunday School outings, circuses, Littlehampton Fair, all feature alongside truancy, harvesting, picking blackberries and primroses, illnesses such as typhoid and diphtheria, and the challenges of the weather. His dedication as a teacher and his belief in the importance of education is shown on every page.

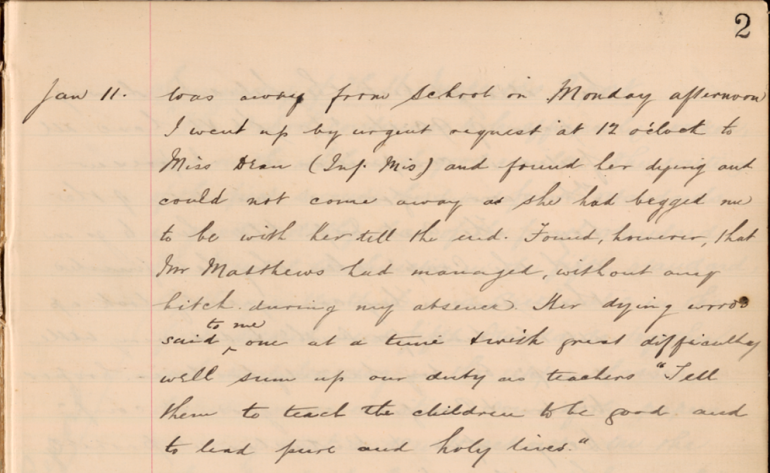

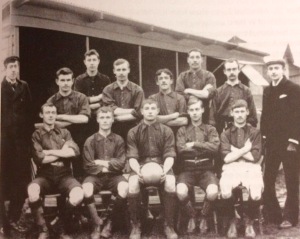

Local history can be traced, noted in concise and colourful detail, and there’s a lot of material here for family historians. Slatford was a close friend of the Vicar, the Rev. Charles Rumball, but that does not stop him from voicing a suspicion that boys were being bribed with drink and tobacco to get them to go to church. Descendants of William Sewell, highly esteemed harbourmaster, can read of the success as a school teacher of his son, also called William. The photo of the Littlehampton football team 1895 to 1896 shows Sewell, and another teacher trained by Slatford on the job as was then the custom, Reg Hale. Hale died in the 1914 – 1918 war, as did many other of Slatford’s former pupils.

Tourism brought many changes, not always welcome to a conscientious teacher: one budding young entrepreneur truanted from school in order to sell strawberries on the beach. Tourism wasn’t all bad however: Herbert Fairweather, whose family was host to the head of a firm of London architects, so impressed the gentleman with the standard of his homework that he was offered a job.

One archive leads to another in the Record Office, and it was helpful that Slatford’s log could be supplemented by related material that doesn’t on first sight seem exciting but can contain interesting gems – Littlehampton Board of Health minutes, for example, revealing that they threatened more than once to close the school down if the sanitation wasn’t improved, and School Board minutes which include an outraged letter to the inspector asking him to explain why he thought discipline was lax. But there wasn’t a photo of Slatford anywhere, and it wasn’t until after the volume was published that his great-great-granddaughter contacted the editor and produced both photos and a lot of information about the family. How vital is the work of family historians!

The log book was published in June this year by the Sussex Record Society, which was set up in 1901 and publishes original records of the county’s history from documents at the West Sussex Record Office, the East Sussex Record Office and in national institutions such as the British Library and The National Archives. Over 90 volumes have been published so far and further details of those in print, online publications and membership can be found on the SRS website. Copies of the Littlehampton School Log Book 1871-1911 by Ruth Brown, from the Sussex Record Society are also available to buy online. The next SRS volume The Letters of John Collier, edited by Dr R. V. Saville was launched at Hastings Museum on Saturday 29 October 2016.

the East Sussex Record Office and in national institutions such as the British Library and The National Archives. Over 90 volumes have been published so far and further details of those in print, online publications and membership can be found on the SRS website. Copies of the Littlehampton School Log Book 1871-1911 by Ruth Brown, from the Sussex Record Society are also available to buy online. The next SRS volume The Letters of John Collier, edited by Dr R. V. Saville was launched at Hastings Museum on Saturday 29 October 2016.

Stay up to date with WSRO – follow us on Facebook and Twitter

I’ve spent several weeks happily immersed in this volume, and have published my observations in my blog: http://established1962.wordpress.com/

I find it difficult to praise Ruth Brown’s work highly enough. There is a fifty-page overview which is a major document in its own right, showing deep understanding and knowledge. There are many explanatory footnotes which speak of countless hours of research, a comprehensive list of sources, and two indexes – one of people, and one of topics. Ms Brown has greatly enriched my own enquiries into elementary schools in the second half of the nineteenth century and I am highly in her debt.

Setting the Scene

School logbooks all date from a government requirement of the 1860s. In fact, they’re by no means rare, and in many cases it’s possible to study them without access to the originals. Several are available as CD-ROMs, and many more in digitised archives; this is one of a small number which have been transcribed and put into book form.

Most of the logbooks I’ve seen come from village schools, the vast majority being under the close supervision of the Rector. Littlehampton Elementary Boys’ School is very different; after the first few years it’s administered by an elected Board. Littlehampton is a town of streets and alleys, with sports clubs and organisations like the boys’ brigade. In country schools boys bring mice from the fields and celebrate May Day with dancing; in Littlehampton there’s a train service to London, and shop-keepers sell nine-year-olds cigarettes or lead shot for their catapults.

Perhaps uniquely, this forty-year logbook is kept by a single person, Thomas Slatford, from the time of his arrival at the age of 23 until his death forty years later. This gives us a consistent narrative and an in-depth picture of the growth of a school over a period of enormous change.

Best of all, Slatford breaks the rules on almost every page. The instructions require that he make “the briefest entry which will suffice” to record routine matters, and that “No reflections or opinions of a general character are to be entered in the Log Book”. In practice plenty of Heads found it beneficial to use the log to vent frustrations, but few went as far as complaining that too many mothers spend their time reading “cheap literature if it deserves such a name”, or recording imputations that boys are being bribed with drink and tobacco – by the church authorities no less – to miss school to sing in the church choir.

Slatford lived in a time of dramatic change. At the start of the nineteenth century Littlehampton was a was a fishing village with a population of just a few hundred, but with the coming of the railway it rapidly grew into a popular seaside resort; indeed, access was so convenient that one of the pupil-teachers at the school could cycle the 65 miles to London. By 1911 the population had grown to some 8000.

Holidaymakers brought great economic benefits to the town, but these came at a cost. Many children ceased attending school in the season to assist parents and employers catering for vast numbers of visitors. Attendance was further hit as visiting attractions – circuses, waxworks, fairs – arrived in town on an almost weekly basis. And there was also considerable deprivation, and unemployment in the winter months, contributing a regular outflow as families emigrated to Canada, the USA, and Australia.

The school perfectly reflected this era of change. In 1871 Slatford was the sole teacher of some 70 boys and his only assistants were older pupils. By 1911 he had moved the school into new and purpose-built premises and he could call upon half a dozen qualified assistant staff to teach more than 300 boys.

Workload

Head teachers had a daunting workload. In smaller schools like Littlehampton in 1871 – s/he would be the only teacher, assisted by one or two pupil-teachers – older pupils who were undergoing an apprenticeship. However committed they were, they were still teenagers learning on the job – and that learning included 90 minutes training and tuition every day, which of course added hugely to the Head’s load.

Even with pupil-teacher help the Head still taught full-time, often taking double or triple classes, and examining every class several times a year to check on their progress. On top of all that, s/he was the only point of contact for every administrative matter – ordering stock, building maintenance, bookkeeping, liasing with parents and visitors, checking on absence and illness….

Here’s a single entry from 1893 (notice the final sting in the tail!): “George James Smart’s sister brought him up and said he had truanted yesterday afternoon. Carpenter (St. I) has been stealing figs from the Manor House garden. Punished him. The Vicar came to tell me that Ellis’s mother could not attend to them. Walter’s father (St. I) has deserted them and so they have gone to a relative at Brighton. Mr Matthews away Tuesday and Friday at Sheffield Park. Collard’s family has small pox. Sent Alfred Muschin (St. I) home, he has a ring worm the sister in the Infant School has been home some time for the same reason. Strudwick (St. II) has gone to Arundel where his father is at work on the Castle. Received notice that Inspection is June 20.”

A Humane Man?

There are many indications of Slatford’s fundamentally humane nature. There is a wealth of feeling behind “it is sad to see some of the little faces so pinched. There is so much want and distress.”

Frequently he promises anxious parents he’ll keep an eye on their son, and he tries to help those who are particularly deprived. “I suppose he has the worst man in the place for a father, an utterly immoral man and a wife-beater. So I have tried to make it as pleasant as I can for the boy but I am afraid he is an incorrigible truant.”

Most obviously, he often prefers to avoid using corporal punishment in favour of talking to the pupil in depth, giving them a second chance, or requiring children to stay behind to catch up on incomplete work. Moreover, he insists that no-one else on his staff may strike a pupil and reprimands those who do – indeed, such teachers often leave soon afterwards.

Nevertheless, keeping discipline was a central feature of Slatford’s work, and he was perfectly prepared to use the cane when he felt it necessary, even when on occasion he recognised it might do no good. As the school expanded, both in pupil numbers and their age (the leaving age was raised twice in the 1890s) the accounts of misbehaviour increase. Truancy (often encouraged by parents and employers), pilfering, stone-throwing and bullying occurred throughout his time, but smoking (“It is disgraceful that children so young should be served with such things. Three for a halfpenny!”), obscenity in the toilets, and the writing of “horrid filth” on paper occur more and more. Even in the last year of his life, however, he is prepared to give a second chance: “The boy turned so ghastly that I did not punish him.”

But his humanity is not the same as ours, and much is horrifying to us. He doesn’t just cane pupils, but records it as ‘flogging’ or ‘whipping’. He doesn’t hesitate to involve the police, and on one occasion ties a boy to a desk until the policeman arrives. On another, he locks two brothers in the cellar.

Illness and even death occur time and time again. It was rather rare for a year not to be marked by the death of pupils, and on one awful occasion he is called to the infants’ school to find their teacher dying. On two occasions – the deaths of his wife and young son – his own family suffers, but his grief is mentioned only briefly, and we never hear anything of his domestic and family life.

He’s more forthcoming about one or two bees in his bonnet – he had a prejudice against cross-eyed boys (“dishonest and untruthful”), and tended to see the railway in a bleakly negative light. He also complained about women being obsessed with soap-opera reading (though this is an indication of a dramatic improvement in literacy, given that in the middle of the century 50% of the population needed to sign with their mark),

A Man Secure in His Own Worth

When Slatford took up his post in 1871 being a head-teacher was an uncertain and not particularly attractive business. The majority of schools were village-based, under the effective control of the Rector, and there was no doubt who was the more important. When the Head called upon the Rector s/he’d be expected to use the tradesmen’s entrance and be sneered at by the Rector’s servants. One rural teacher complained in 1879 that he was regarded as “the parson’s fag, squire’s doormat, church scraper, professional singer, sub-curate, land surveyor, drill master, parish clerk, letter writer, librarian, washerwoman’s target, organist, choir master, and youth’s instructor”.

Just as important in a Head’s life would be Her Majesty’s Inspector, and the report on his annual visit to assess both the pupils and the teaching. Many HMI saw themselves as socially and intellectually superior to a mere teacher, and weren’t slow to make this clear.

I’ve not come across any other Head who felt so secure that he didn’t need to worry about either Rector or Inspector. He was acquainted with the Rector since his days as a pupil-teacher, and they’d stayed in contact both while Slatford trained at Culham College and during his first job at Falmouth. It was at the Rev. Rumball’s direct invitation that he came to Littlehampton.

In 1883 at least one Head was so intimidated by the inspection process that she committed suicide, but Slatford’s relations with the Rector, and with the School Board, were so solid that he was prepared to challenge HMI head on. HMI reports had always been good until an unfortunate and, I suspect, unique incident in early 1884. At the end of the visit the inspector’s assistant is hit by a missile from a catapult! Slatford desperately records how agreeable the inspectors are, but the damage is done, and the report says – not surprisingly, that better discipline should be maintained.

Moreover, the inspector has a long memory, and in the next several years discipline is criticised time and again. Eventually, Slatford snaps and he writes some 200 words where the fury still shines through today: “We all feel the sting of having a sore continually probed and we work on through the year like hounds fearing the lash.”

At his prompting, the Board very politely asks the Inspector to indicate “particulars you consider the discipline is defective … if you would make any suggestions for its improvement, for the School Board, as well as the Head Master, are most desirous that all cause of complaint should be removed and the school restored to a thoroughly good state of discipline.”

The Inspector’s reply is lost but the effect is explosive, and he resigns later in the year. Subsequent inspectors are much more positive, and point out that with four classes in a single undivided room with appalling sonic characteristics the “resonance and din were almost unbearable”. Indeed, before long, HMI are demanding that more suitable premises are found. The demand is repeated, and a later report says tersely “School visited – I hope for the last time in these premises.”

And though he’s always receptive to constructive requests from parents, he gives no ground in more confrontational situations. To a father who criticises his arithmetic teaching he replies that Slatford doesn’t tell the man how to lay bricks and he’s not prepared to accept “impertinent interference”. Another critical father threatens to hit him, saying he’s quite prepared to pay the fine. Slatford doesn’t give an inch and the parent ends up “asking me to be as kind as I could as he had been delicate lately”!

Teachers and Curriculum

For any teacher following the changes in school and curriculum is immensely fascinating. At the start of Slatford’s career teaching focuses totally upon the narrow demands of the Revised Code’s insistence upon reading, writing, and arithmetic – and nothing more. By the time of his death, the range of subjects has been expanded, the leaving age has been raised, and the introduction of a more advanced Standard VII in 1882 meant schools offered a curriculum similar to that in lower secondary years today.

In science alone we learn of an explosion when making hydrogen in 1901, while another teacher suffers burns when experimenting with phosphorus. (I did the same experiment on teaching practice, with much the same result. I recall saying “Please excuse me a moment, my hand seems to be on fire”). Incidentally, by 1910 the inspectors are recommending that there should be fewer demonstrations, with the pupils performing more experiments for themselves.

Slatford was no stick-in-the-mud. He was a member – and I imagine this was rather unusual – of the National Union of Elementary Teachers (the forerunner of the NUT). He welcomes opportunities for outdoor lessons – gardening, drill, and sending the young pupils of Standard I “to go out and map some of the streets around ….”

In 1896 he tells a pupil-teacher that his lesson was “too much an ‘instruction’. …. I have asked him to let the children work out more for themselves.” (More than a hundred years later, most of our recent Education ministers have believed there should be a lot more instruction, and that there are far too many children working things out for themselves.)

When the Education Department recommends the application of kindergarten methods with younger children he quickly arranges for his wife to give some lessons to boys in Standard I. (She was a Head herself and she was far more forthright than him, describing the national curriculum of the time as ‘ridiculous’.)

Subsequently we read of the smallest children having a dolls’ house and other toys, and before long he is convinced of the value of women teachers with his younger pupils – by the time of his death there are three long-term women on the staff and he regards them very highly.

In his first years Slatford at Littlehampton was the sole qualified teacher, and insisted that lessons were conducted according to his thinking and his alone. He is highly critical that his pupil-teacher Raymond Gibbs shows too light a touch with his class, and is furious when another, Horace Boswell, suggests that Standard I boys cannot yet use a ruler accurately. “This, I of course said, was not his business he was here to carry out my wishes not to criticise or express opinions on them. He works hard with the class but is a little too opinionated perhaps.”

In fact, both Gibbs and Boswell proved to be outstandingly successful pupil-teachers, the very best in the whole county. Slatford’s record with pupil-teachers is exceptional; they often come back to see him and their pupils are pleased to see them – “their faces so brightened …”.

This isn’t the only entry to show Slatford wanted schooling to be more than the imposition of curriculum tuition upon reluctant pupils. For many of those at school in the second half of the nineteenth century school was something forced upon them, and which they disliked intensely. I was hugely interested to pick up little fragments showing that Slatford tried for something more. He mentions teaching boys to play draughts in the lunch period, and that a pupil-teacher plays with his boys after school.

After 21 years at the school he muses that he tries to make “… a place where the paths of learning are paths of pleasantness too.” One Christmas he goes round school and is impressed by the number of Christmas cards pupils have given their teachers, as “evidence of kindly feeling between them”.

In 1911, the final year of his life, he goes further. A mother says her son is worried about Science “though he is fond of it and very fond of his teacher.” Slatford speaks to the teacher and reports back to the mother “he must make a friend of his teacher and that we want children to ask questions.”

I was reminded of what the educationalist H C Dent, wrote – and it was teachers like Slatford he was talking about – “Some teachers even dared to think that they and their pupils should be friends, not foes, should work with, not against, each other; and they initiated the most profoundly important transformation of the English elementary school, from a place of hatred to one of happiness.”

LikeLiked by 1 person

Brilliant book, and lovely to meet Ruth Brown when at the Record Office while researching the log books for Hollycombe School which I am transcribing.

LikeLike

I agree – a terrific book reflecting a huge amount of scholarship and commitment. I too have researched several logbooks and would be delighted to share experiences. I’d be happy to hear from you if you wanted to make contact. Regards, Alan Parr, arparr “at” gmx “dot” com

LikeLike