By Nichola Court, Archivist

In 2008, WSRO purchased at auction an item listed as ‘a “flapper’s” social diary’ (catalogued as AM 75/1). Although the diary is short, covering barely three months, the auctioneers noted that the diary included several references to Chichester and Oving, hence WSRO’s interest in the document. The volume was somewhat mysterious as there was no indication as to the writer’s name or its provenance, leaving us with something of a challenge if we wished to try to identify the gregarious, lively and highly privileged ‘Self’. This task was recently taken on by two of our willing volunteers, Anna and Sue, who usually help us with our school programme; and, after many hours of painstaking research, they were able to identify ‘Self’ as Miss Luise Rosemary (Rosie) Kerr. This blog is the first of two which look in detail at the diary and its creator; the second part will explore how the mysterious author’s identity was revealed.

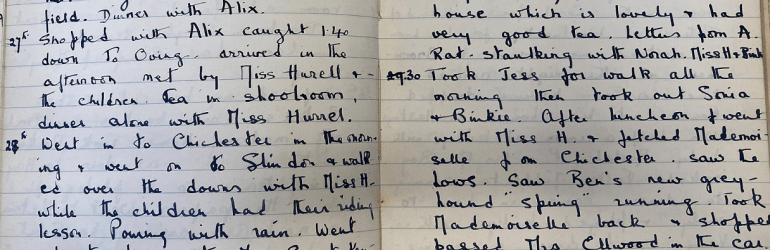

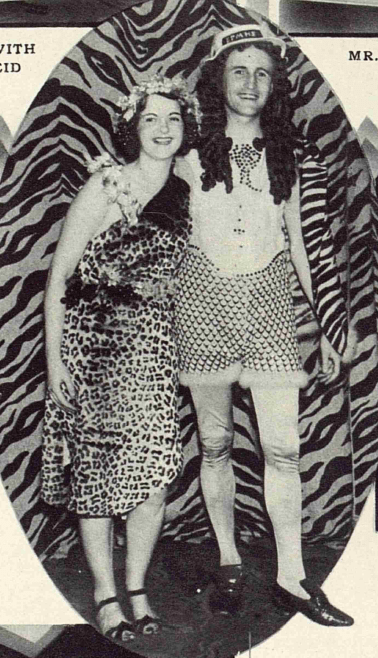

Born on 22 November 1908, Luise Rosemary ‘Rosie’ Kerr was the youngest daughter of Admiral Mark Kerr and Rosemary Margaret Gough; her father had a distinguished Naval career and was connected to royalty through his father, Admiral Frederic Kerr, who had been Groom in Waiting to Queen Victoria. Rosie’s mother, Rosemary, helped to pioneer the Girl Guiding Movement and their elder daughter, Alix (born 1907), was also heavily involved with the movement. The Kerrs were wealthy, well connected and enjoyed an active social life, and, short lived as it is, there is plenty of evidence to support this in the diary; there are ski trips to Klosters, frequent trips to the theatre or the ‘flicks’, dinners, teas and luncheons, bridge games, shopping trips and hair-raising car rides across London, and plenty of late nights – or early mornings, depending on your viewpoint. Scattered amongst these are throwaway references to the weather, hair washing (an event worth noting), being photographed by Hay Wrightson (one of the leading Society photographers), and her sister’s car crash (an event which would prove to be the key to identifying Rosie as the author). As a lady of leisure, Rosie was able to chose to stay in bed all day, should there be nothing much worth getting up for, and she certainly didn’t need a conventional job; any occasional reference to work, writing or trips to the office are in relation to her role on the Women’s Conservative Entertainment Committee, and not to any form of paid employment.

As a member of high society, Rosie appeared frequently in magazines such as Tatler in the 1920s and 1930s. It is believed that Rosie was engaged to the pilot Jacques-Henri Schloesing, who was fatally shot down on 26th August 1944. Prior to this, Schloesing – who, despite being French, had joined the RAF – had suffered severe burns to his face and left wrist after engaging in combat whilst flying a Spitfire over enemy territory; after two months, he escaped to England with the support of the French Resistance, where he was treated for his burns at Queen Victoria Hospital in East Grinstead by the pioneering plastic surgeon, Sir Archibald McIndoe. The Queen Victoria Hospital Archives, including the so-called ‘Guinea Pig Club’ files, are held at WSRO, and these include Scholesing’s file; alongside his medical notes and photographs is a letter referencing his relationship with Rosie. After the war, Rosie continued to move in high circles and appeared again in society magazines, but she remained unmarried for the rest of her life, until her death on 14th September 1985.

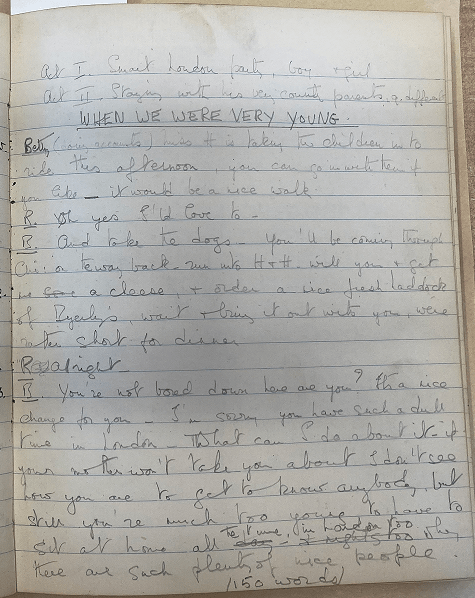

Although short, Rosie’s diary provides a fascinating insight into the busy, dizzy life of a wealthy, well connected woman at the end of the 1920s, and the society in which she lived. In addition to her daily life, she also used the diary to record a list of ‘men’ and ‘girls’ to invite to her 21st birthday party, a further list of ‘men for parties’, and even jotted down a script for a play. Reflecting her apparent love for the theatre, the play is entitled ‘When We Were Very Young’, with Act I taking place at a smart London party, featuring a boy and girl, and Act II set with his ‘very country parents’, with whom they are staying (this setting is noted as ‘quite different’); the diary appears to include the start of Act II, at the country parents’ house in Chichester: perhaps a case of art imitating life!

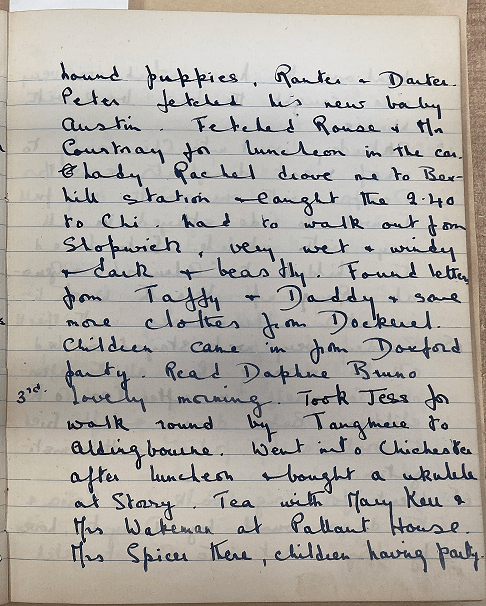

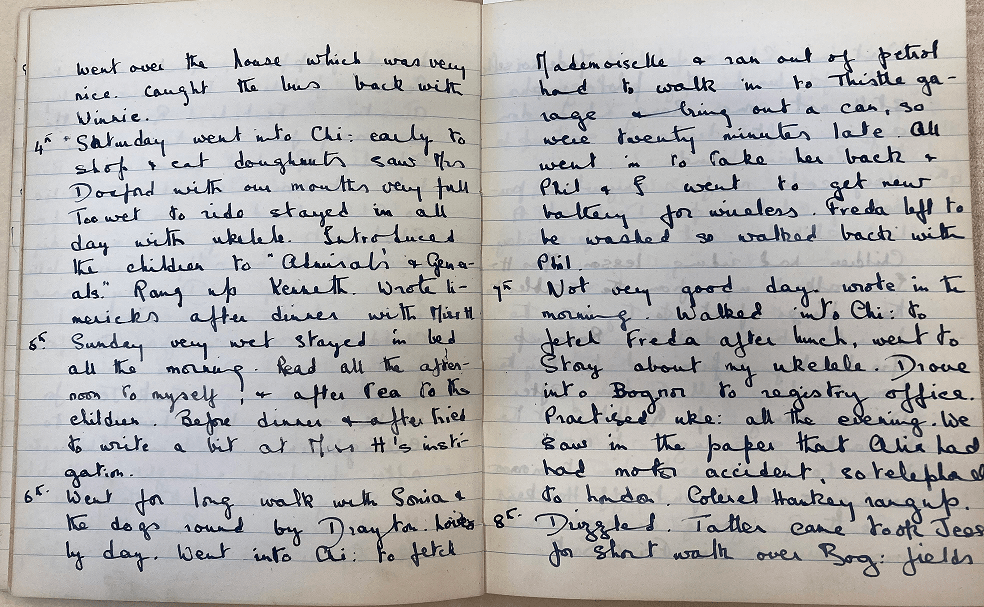

At a local level, the diary includes reference to Rosie’s visit to Oving in 1929, where we believe she stayed with family at Oving Manor House. Despite the very wintry weather, she goes for long walks in the countryside, to places such as Slindon and Aldingbourne, motors further afield to Binderton and the Trundle, and heads into Chichester or Bognor on various errands; on one trip to Chichester, she even runs out of petrol and has to walk out to ‘Thistle garage’ to get some in a can. Perhaps most intriguingly, Rosie notes a trip to Chichester to eat doughnuts and – succumbing to the 1920s craze for the musical instrument – buy a ukulele! There are a few more references to the ukulele and several weeks later, she notes playing the ukulele with her friends in London.

Rosie’s diary is a fun and engaging record and very evocative of the era it depicts, which perhaps feels familiar to some of us thanks to the ongoing popularity of authors such as Agatha Christie, featuring friends and relatives known by nicknames such as Taffy and Puff, various escapades and high jinks, and luncheons at high class restaurants.

Next week, to conclude our look at Rosie’s diary, volunteers Anna and Sue detail their research journey and explain how they identified Rosie as the anonymous author of the flapper’s diary.

To find out more about our school programme and access free resources, click on the link to visit our page on the West Sussex Services for Schools website, https://schools.westsussex.gov.uk/Services/6363.

You can find a number of articles about the Queen Victoria Hospital Archives and the Guinea Pig Club on our blog: just search for Queen Victoria Hospital or Guinea Pig Club.

Stay up to date with WSRO – follow us on Facebook, Instagram, Twitter and YouTube

One thought on “‘Who’s that girl?’ The anonymous diary of a 1920s flapper (part 1)”