By Alice Millard, archivist

Before Haiti was so named it was called Saint Domingue, having been colonised by the Spanish in the 15th century then controlled by the French in the 17th century. As with most other Caribbean islands at the time, Saint Domingue’s economy was dependent on produce from plantations. In fact, the quantities of sugar and coffee it exported to Europe far outweighed the amount of those products which were generated by British colonies. The vast majority of those who toiled on these plantations were enslaved people trafficked from Africa and their descendants who were born into slavery.

One night in August 1791, thousands of enslaved people attended a vodou ceremony during which anger over the state of the colony after the French Revolution and the systemic injustices of a racist society bubbled over and an insurrection took place. The enslaved took control of much of the island, with extreme violence enacted on both sides. The rebellion was orchestrated by a number of formerly enslaved men but one in particular, Toussaint Louverture, led the cause.

Toussaint continued to lead the revolution over eleven gruelling years until Napoleon Bonaparte sent 43,000 French troops to capture Toussaint. He was transported to France where he died in prison in 1803. He left a wife and two sons, all of whom were spending most of their time in France. It is important to note that Toussaint, whilst not being a household name necessarily, was still well known across Europe as the driving force behind the emancipation of enslaved Haitians. His name had regularly featured in British newspapers as news of his activities travelled across the Atlantic.

So what has the mastermind behind the Haitian revolution got to do with Chichester? In 1814, a young man claiming to be Toussaint’s son, also called Toussaint, was staying in the city under the ‘protection’ of a certain Mr Henry Hobbs. Hobbs was a merchant and lived in Friary Close in Friary Lane, Chichester; a very large house by all accounts, and Hobbs was a wealthy man. He was also connected to the local Quaker families of Hack and Barton and it’s very possible he was also a Quaker. The Hacks were well known as anti-slavery campaigners.

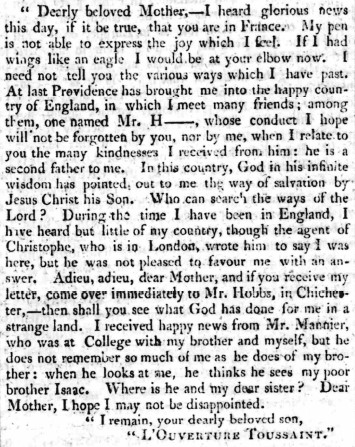

In September 1814, Toussaint Jr entreated Hobbs to publish a letter on his behalf in the London Courier and Evening Gazette. Hobbs prefaced the letter:

“Sir – Toussaint L’Ouverture, son of the late Toussaint of St. Domingo, and now under education in this country for the missionary service, having had assurances from a Gentleman lately come from France, that his mother is still living in that country, has entreat me to procure the insertion of a letter to her in your paper, in hopes that some of your readers, who may have means and opportunity, will kindly interest themselves to ascertain the fact. I am, Sir, Your most obedient servant, H. Hobbs. Chichester, Sept. 24, 1814.”

In his letter, Toussaint Jr entreats his mother to “come over immediately to Mr Hobbs”. He also includes some interesting details such as his love for God, his agent called Christophe, someone called Mr Mannier who he was at college with, and his brother Isaac and sister (nameless). He appeared to be the real deal.

However, as recounted in a letter written by Priscilla Tuke to Elizabeth Hack in 1816 (Add Mss 49717/11), Hobbs – who had been like a ‘second father’ to him – had grown unsure that Toussaint Jr was who he claimed to be. In the letter, Tuke reveals that Hobbs and others had formed a committee to devise ways in which Toussaint could inadvertently “unmask” himself. He did exactly that. Hobbs was right.

Tuke goes on to explain that the man claiming to be Toussaint Jr was not the son of General Toussaint, but had instead confessed to being the son of a man called Jean Pierre, a close ally of Toussaint. Sadly, a surname for this gentleman wasn’t recorded and neither was the true name of this pretender. History has held on to the names of other Haitian revolutionaries, and there are indeed men called Jean Pierre connected to Toussaint Louverture. However, with so little information to go on, finding any proven links is unlikely.

‘Toussaint Jr’ hadn’t just deceived Chichester, though. In a copy of a letter written in November 1814 and held at the Norfolk Record Office (MC 64/17), nonconformist pastor John Goulty of Surrey writes to W H Pattisson of Essex (who had, amongst many others, taken an interest in this man) about the incident. In it, Goulty explains that a committee of people, including Henry Hobbs, had been set up to establish his claim. This committee had reported to the directors of the Missionary Society, who had been overseeing his upkeep, and ‘Toussaint Jr’ had been summoned to a meeting in which they informed him of the withdrawal of their patronage.

Unfortunately, neither letter offers any leads as to what happened to this man after the truth was revealed. Regardless of the eventual outcome, the event offers us some insight into the activities and attitudes of nonconformists in England in relation to anti-slavery. On the one hand, clear networking of people around the country meant that this gentleman was well supported. Yet why they did not continue to support him in some fashion afterwards also raises some interesting questions. It is a very odd story with few answers, but it’s a fascinating glimpse into the goings-on in Chichester at a tumultuous time in Georgian Britain.

Stay up to date with WSRO – follow us on Facebook, Instagram, Twitter and YouTube