By Jenny Bettger, Archives Assistant (Research)

While producing research guides for Quaker and English Civil War records in the Record Office archive I came across the memories of Mary Pennington (MP 3899 and MP 1875), which refer to both the Siege of Arundel and her faith. Mary’s first husband Sir William Springett (or Springate) fought in the English Civil War and died following the Siege of Arundel. She and her second husband Isaac Pennington (or Penington) were both early Quakers. Personal accounts from women in this period are rare. On reading the section which relates to the civil war I was amazed at the details it contained and the immediacy of her writing, despite the passing of time.

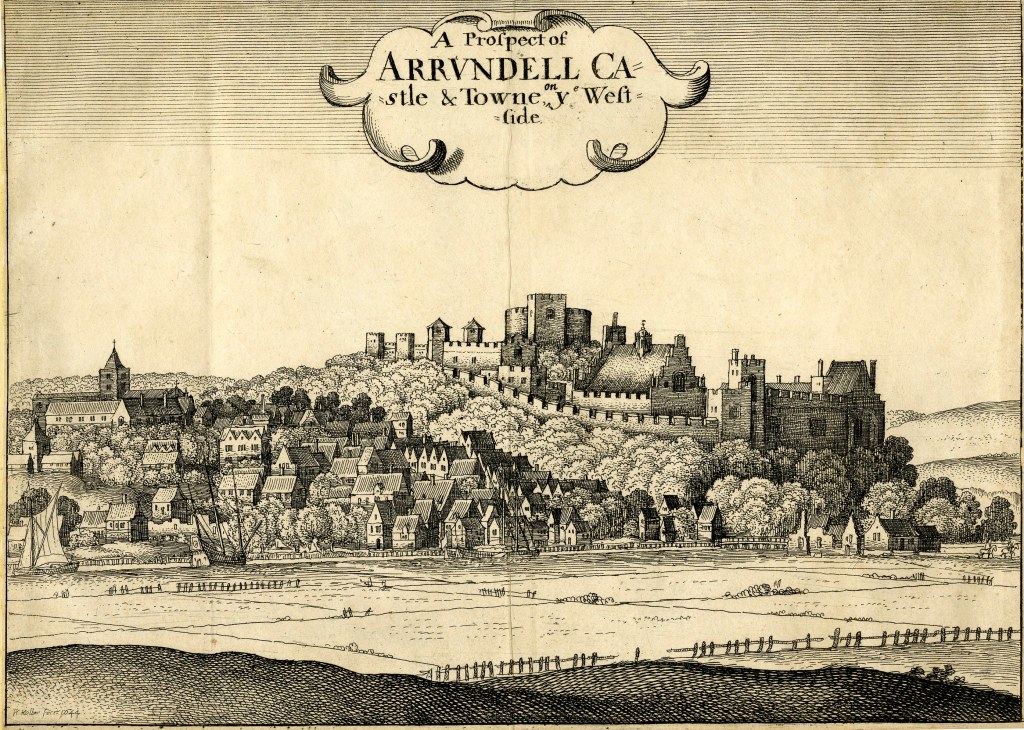

First some background on the Siege of Arundel, which occurred in the winter of 1643-1644. Arundel with its castle was an important defensive stronghold during the English Civil War and changed hands several times with the Parliamentarians maintaining a garrison from 1642. On 6th December 1643 a Royalist army led by Lord Hopton arrived at Arundel and took control of the town. The Parliamentarian garrison retreated into the castle and after a short three day siege the castle fell to the Royalist forces. Only a few weeks later, Sir William Waller’s Parliamentarian army arrived and began a siege to regain control of Arundel and its castle. Lack of supplies, illness and the defeat of a relief force led to the surrender of the Royalist garrison on 6th January 1644.

Mary’s husband William Springett was a commander of a Kentish regiment for the Parliamentarian army during the siege and put in charge of the garrison after it was recaptured. Many of the troops including William fell ill ‘with a disorder that was then among the soldiers (called the calenture)’ [a feverish delirium]; later sources identify the epidemic as typhus. His condition was so serious that Mary was sent for and unlike the ordinary soldiers, the Springett family had the resources to have a doctor brought with her from London. Mary was heavily pregnant at the time and although this and the season were an obstacle to travel, the ongoing war does not appear to have even been considered.

I was then at London and great with child, which rendered my undertaking such a journey very difficult, besides which the waters were in several places so high as to be almost impassable, which the coachmen were so sensible of that they refused to convey me down.

After securing another coachman willing to transport her, she set off with her servant and a doctor. Although the account does not indicate how long it took to travel from London to Arundel it was likely several days. Mary describes it in her account as a ‘tedious and dismal journey…the waters were so deep in some parts of the high road that we were obliged to pass in a boat, taking our things with us, while they tied strings to the horses bridles and swam the coach and horses through.’ Nearing Arundel late at night Mary’s determination to reach her husband outweighed calls from the coachman to complete the journey the following day.

I was resolved not to get out of the coach unless it broke, or until I came so near the house that I could complete it of foot, so finding my resolution he pressed on.

The impact of the fighting on the town can be seen in her description:

When we came to Arundel, everything wore a dismal appearance, the town being dispopulated, all the windows broke, with the great guns and the soldiers making stables of all the shops and lower rooms, and there being no other light in the town but what came from these stables.

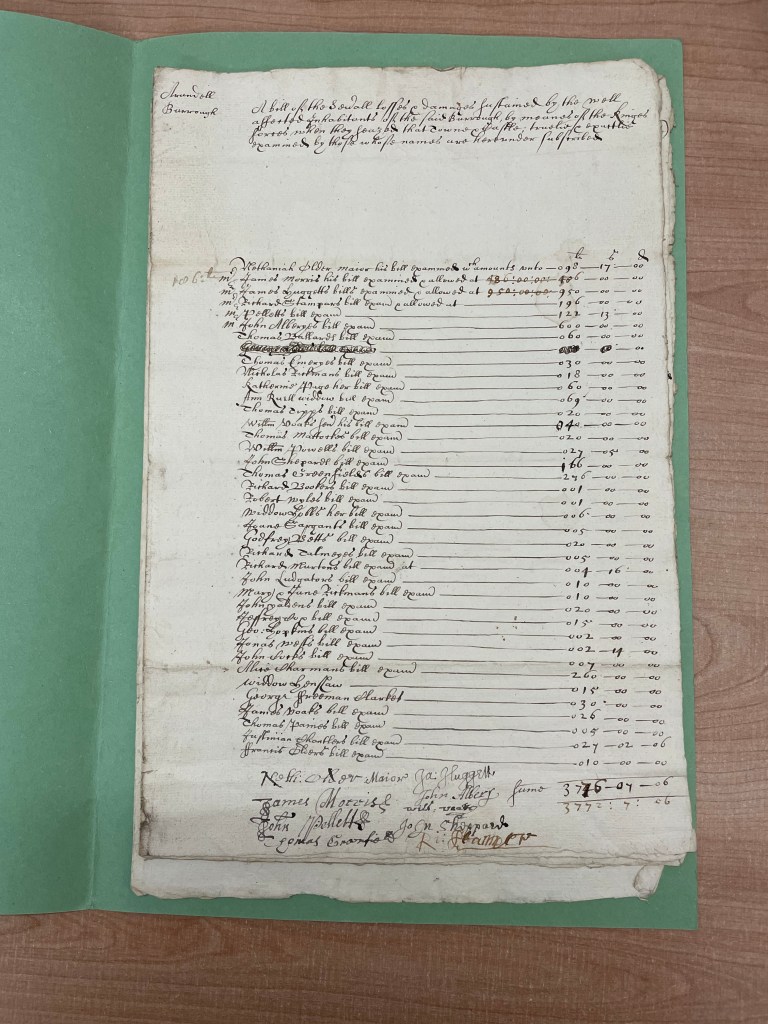

Our archive also holds papers concerning compensation for civil war damage for Arundel (Arundel Borough/M9) from c1645-1649. These include a petition to parliament and a list of inhabitants with the value of the damage they are claiming. The total amount claimed comes to over £3700, which is around three quarters of a million pounds in 2024. As the claims are only for damage done by the King’s forces it is likely that the real total was much higher.

Mary’s account then goes on to describe her reuniting with William, who is in bed struggling with a fever and delirious. He calls to her ‘let me embrace thee before I die! I am going to thy God and my God.’ William seems greatly relieved by Mary’s presence; she describes many hours of her sitting at his bedside although the doctors advised against it: ‘because the infection was so high that they thought I endangered both myself and the child by taking so much of his breath.’ Even with the treatment of the doctor his condition continued to deteriorate and he died aged about 23. Mary movingly recounts some of his last words:

“Come my dear let me kiss thee before I die” which he did with such earnestness as if he would have left his breath in me, then he said again “come once more let me kiss thee and take my leave of thee” which he did in the same manner as before, saying “now no more, never no more.”

Following William’s death his body was taken to his home parish of Ringmer in East Sussex. His burial is recorded in the parish register on 28th January 1643 [1644 modern dating] as ‘that religious and valiant knight Sir William Springet.’ Their daughter Guilelma Maria Posthuma Springett was born the next month, named after both parents with her name also indicating she was born posthumously. Later Mary discovered that William had left debts of about £2000 (around £400,000 in 2024), which he had accrued due to his military expenses. Mary went on to marry Isaac Pennington in 1654, around the same time they both became Quakers. Guilelma married William Penn, the founder of the state of Pennsylvania, in a Quaker ceremony in 1672. Mary’s memories were written for their son Springett Penn around 1680, shortly before her death.

To find out more about the English Civil War and Quaker records available at the Record Office, please see our research guides:

Stay up to date with WSRO – follow us on Facebook, Instagram, Threads and YouTube

One thought on “The Siege of Arundel and The Springett Family”