By Lois Bodie, Archives Assistant

The Battle of Quebec, also known as the Battle of the Plains of Abraham, took place on 13th September 1759 and, since reading about it several years ago, it has stayed stuck in my mind. Upon starting at the Record Office, I was excited to learn of a Sussex connection and that we even hold documents relating to it.

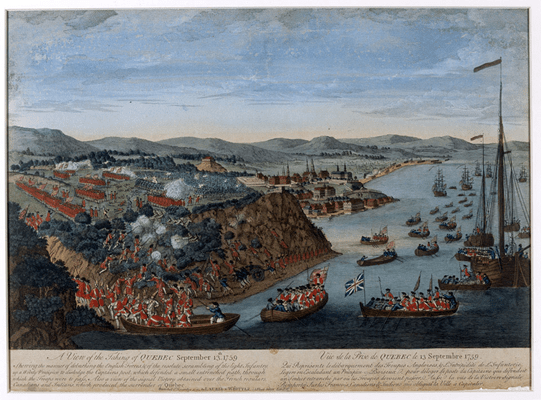

The battle was fought at Quebec – at that time the capital of New France –between British and French forces. For years, these two powers had been vying for control of North America, and Quebec proved to be a decisive moment, both in the French and Indian War (1754-63) and the future of the continent: it saw the end of French rule in Canada, and despite the British victory, sowed some of the seeds of the American Revolution to come. To me, the battle conjures up quite the image, for its success depended on British light infantry scaling a near vertical cliff face to the city above, with nothing but tree roots to hold onto in the pre-dawn gloom.

© National Army Museum

In the weeks prior to the battle, however, victory seemed a far-off prospect. The mood was sour: the British troops had been there several months and while great swathes of the city had been burnt, they were no closer to taking it. The French could not be lured outside the city walls and the weather was on the turn, with Captain John Knox of the 43rd Regiment of Foot writing, ‘[The wind] blows fresh down the river. Mornings and evenings raw and cold.’ Disease ran rampant through the British army, seeing General Wolfe, commander of the British force, himself become temporarily bedridden. The chance of taking Quebec grew slimmer each day, and with winter creeping closer, the St Lawrence River would soon be unnavigable. A decision whether to strike or retreat had to be made, and quickly.

It was determined that light infantrymen led by Lieutenant Colonel Howe would be the first to slip across the St Lawrence River towards the city and once disembarked, proceed to clamber up the cliff as quiet as could be. It was so impractical a route that the Marquis de Montcalm, commander of the French army, had left defence of the summit to a very small force. Meanwhile, further up the river, a diversionary attack would be launched.

Among the regiments present at the battle was the 35th Regiment of Foot, which would later merge with the 107th to become the Royal Sussex Regiment. The 35th Regiment was heavily involved in the conflicts in North America in the mid-18th century, having already been caught in the massacre at Fort William Henry and fighting at the siege of Louisburg. The 35th suffered great loss at the former, the men defending not only themselves but their wives and children (in 1960, a plaque dedicated to the regiment was raised at the site, commemorating their bravery). With the regiment mostly recovered and the plan of action for Quebec decided, the 35th, under the command of Colonel Otway, was to be part of the second landing.

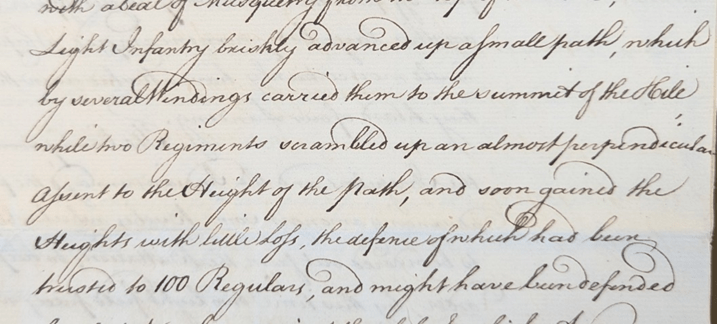

At the Record Office, we have documents relating to the battle, in both the Royal Sussex Regiment and Buckle collections. They provide plenty of detail on the ascent up the cliff and the demise of the much-loved General Wolfe. As seen in Buckle Mss 207, the men ‘scrambled up an almost perpendicular ascent to the height of the path, and soon gained the Heights with little loss’. It was a feat that would later become one of Britain’s most celebrated military achievements.

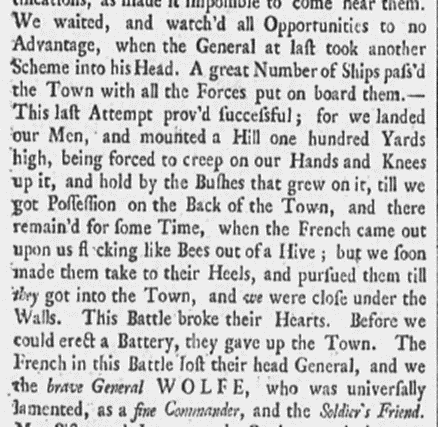

An eyewitness account of a soldier in the 35th Regiment exists in the form of a letter written to his parents, published in The Derby Mercury at the end of 1759. It describes how, once the summit had been gained, ‘the French came out upon us flocking like Bees out of a Hive’, shocked at finding themselves under attack after months besieged, before they turned on their heels and ran back to the city. Wolfe’s men followed in hot pursuit.

© The British Library Board. All Rights Reserved.

Consequently, by 8 o’clock that morning, Wolfe’s entire force had successfully assembled on the Plains of Abraham above. The battle to come would take less than an hour and would ultimately see the deaths of both its commanders.

In Buckle Mss 210, the fury of the fight is described as follows:

“[T]he French fought with Great Bravery a long while, But our Soldiers Fought like Lions, Rush’d on them with fix’d Bayonets, Routed and pursued them to the walls of the City, Killed numbers in the Ditches … The Brunt of the action fell on Braggs [28th Regiment], Lascelles [47th], Anstruther’s [58th] and the Highlanders [Fraser’s Highlanders]…and to the Great Honour of the Highlanders, and Lascelles, the Former had not a Broad Sword, nor the latter a Bayonet, that was not stained with the Enemy’s Blood.”

The 35th Regiment was pivotal in the outcome of the battle: they successfully overcame the grenadiers of the French Royal Roussillon Regiment and took the white feathers from their hats as trophies. It would not be long before the white plume was incorporated into the 35th’s cap badge; and, much later, there would be a nod to this historic moment, for in 1958, the army barracks of the Royal Sussex Regiment in Chichester were renamed the Roussillon Barracks.

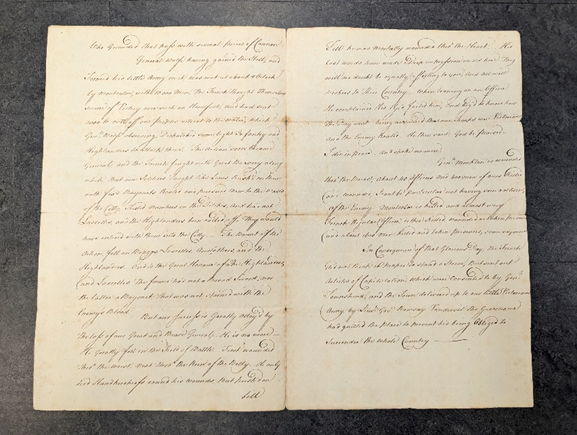

However, as seen in the transcript of the soldier’s letter above, the British felt their victory was marred by the loss of General Wolfe, much admired among his troops. Buckle Mss 210 expands on this further:

“…our success is Greatly alloy’d by The loss of our Great and Brave General. He is no more. He Greatly fell in the Field of Battle. First wounded thro’ the wrist, next thro’ the … Belly. He only tied Handkerchiefs round his wounds, but push’d on Till he was mortally wounded thro’ the Heart. His last words have made a deep impression on us here. They will no doubt be equally affecting to you, and all well wishers to Their Country…when leaning on an Officer He complained His eyes failed him, and beg’d to know how the Day went, being answer’d that our Troops were Victorious and the Enemy routed…He then said, God be praised…I die in peace…and spoke no more.”

RSR/MSS/1/19

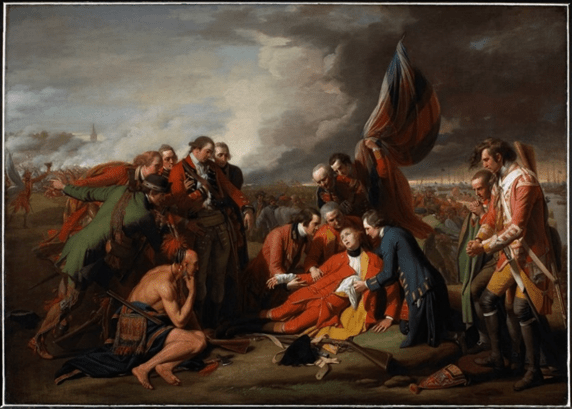

News of Wolfe’s death reached Britain in October, and he became an immediate sensation. The fact that he died at the moment of victory earned him the reputation of a patriotic martyr; his likeness was immortalised in paintings and prints, the most famous being ‘The Death of General Wolfe’ by Benjamin West (1770). Later, it would become one of the most recognisable paintings of the 18th century.

© National Gallery of Canada, Ottawa

Following the French surrender of Quebec, the 35th Regiment took part in the invasion of Martinique (1762) and capture of Havana (1762), before sailing back to Britain in 1765. They would soon be back on the shores of North America, however, fighting at Bunker Hill (1775), Long Island (1776), White Plains (1776) and Harlem Heights (1776) during the American War of Independence.

Incidentally, the Battle of Quebec can claim some responsibility for sparking this conflict to come: with the removal of the French threat, Britain inadvertently undermined its own role as a ‘protector’ to the colonists, and the heavy taxation that followed the French and Indian War only stirred resentment towards British governance. While it may have escaped most people today in favour of more famous battles, the events of 13th September 1759 undoubtedly sent cracks running through the foundations of North America and changed the course of history, preceding the ‘shot heard round the world’ by no less than sixteen years.

With several generations of the Buckle family serving in the Royal Navy, the Buckle papers span the globe and are an incredible window into Britain’s involvement in overseas affairs. You can find out more about the Buckle family here and explore the collection firsthand here.

Stay up to date with WSRO – follow us on Facebook, Instagram, Threads and YouTube