By Alice Millard, Archivist

T

o mark the recent upload of the Graylingwell Hospital Archive catalogue to our website, this blog will dip into the vast history of this significant hospital through its archives.

Founding

Before the establishment of lunatic asylums in the mid-19th century, people living in poverty with mental health issues were dealt with locally under poor law, vagrancy law or criminal law. They were therefore likely to end up in workhouses, houses of correction or prisons. Under the Lunacy Act 1845 and the County Asylums Act of the same year, it became compulsory for counties to have lunatic asylums and the Lunacy Commission was established regulate them.

Graylingwell Hospital had its foundations in both the Lunacy Act and the creation of West Sussex in 1888, after which the West Sussex County Council (WSCC) was formed and became responsible for providing care for the mentally ill. This, although a distinction wasn’t understood at the time, included those with learning disabilities and conditions such as dementia.

After a period in which an arrangement with East Sussex County Council meant patients from West Sussex were sent to the Sussex County Asylum in Haywards Heath, WSCC bought Graylingwell Farm with the intention of building the county’s own psychiatric hospital and construction began in 1894.

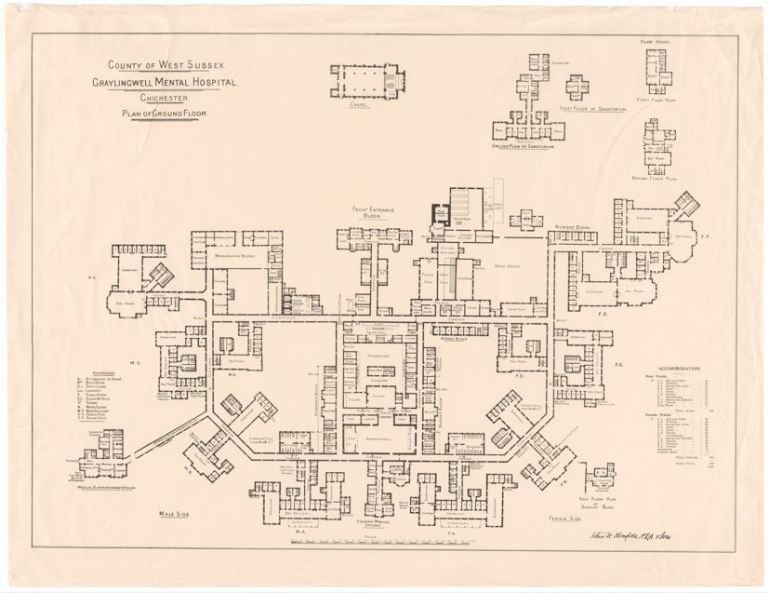

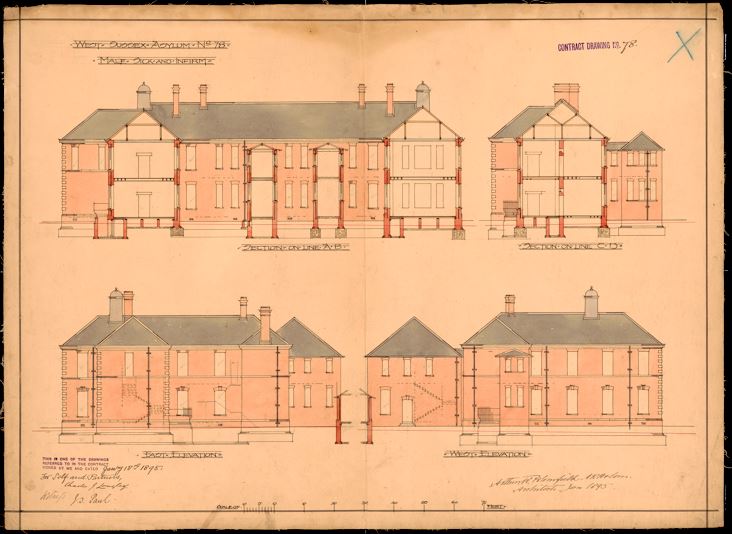

Opened in 1897 as the West Sussex County Asylum, it became known as Graylingwell Hospital a year later. Designed by renowned architect Sir Arthur Blomfield, the hospital is in the Queen Anne style and constructed in warm red Cranleigh brick with large windows, a feature which, at the time, was popular in new hospitals.

Dr Harold Kidd

The first Medical Superintendent at the hospital was 32-year-old Dr Harold Kidd, who began his work in 1896 at the semi-constructed site. Dr Kidd was a graduate of St Mary’s Hospital and was determined to enter psychiatry. He followed a humanistic approach to psychiatric care and believed that Graylingwell was not to be a place of ‘confinement’, but rather a hospital in which patients could be treated and discharged.[1]

In February 1900, Dr Kidd appointed a replacement Assistant Matron named Mildred. Mildred was 24 years old and had grown up at HMP Parkhurst, a notorious prison on the Isle of Wight, where her father had served as governor. Over the next three years, a relationship developed between the colleagues, and Mildred resigned in March 1903 to become Mrs Kidd. At the time, married women could not work as staff nurses.

[1] https://eprints.chi.ac.uk/id/eprint/2527/1/001-030%20SouthernHist38%20Wright.pdf

Dr Kidd resigned in 1926 after thirty years at the hospital. He died just three years later in 1929, aged 65, and is buried in Portfield Cemetery, Chichester. His headstone quotes Epilogue by Robert Browning,

“One who never turned his back but marched breast forward,

Never doubted clouds would break,

Never dreamed, though right were worsted wrong would triumph,

Held we fall to rise, are baffled to fight better,

Sleep to wake.”

Early years

Throughout his term as Medical Superintendent, Dr Kidd oversaw the growth of the hospital into a fully-fledged institution. As a psychiatric hospital built towards the end of the Victorian era, Graylingwell featured advancements in early psychiatry which had developed through the 1800s. Graylingwell’s planners absorbed ideas pioneered by earlier asylums; there was no practice of routinely restraining patients, and it emphasised the importance of therapeutic environments. Graylingwell had large grounds featuring gardens and a working farm. Staff also laid on entertainment and social events for patients. In a time before the kind of psychiatric knowledge we have today, this sort of environment was thought to provide patients with opportunities for recovery.[2]

[2] https://www.sciencemuseum.org.uk/objects-and-stories/medicine/victorian-mental-asylum

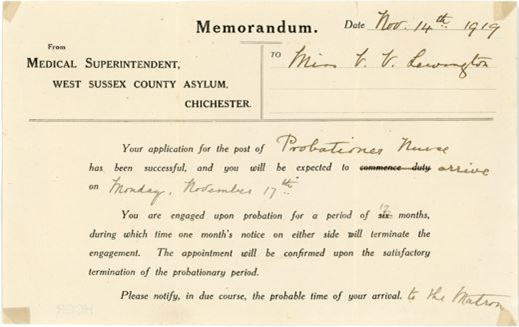

A particularly significant change in attitude concerned the training of staff. In pre-Victorian asylums, attendants were often more like ‘keepers’ and lacked nursing skills. However, Graylingwell’s roster had both male and female nurses specifically trained for ‘mental nursing’. The archive includes various registers of nursing staff from 1897 into the 1970s. It also includes the papers of one early nurse, Violet (Vera) Lewington.

Born and raised in Chichester, Vera joined as a probationary nurse in 1919, having grown up with the newly established hospital just a mile away. She became a registered nurse in 1925. After her marriage to fellow nurse Joseph Searle in 1927, Vera moved away, and she and her husband became matron and superintendent of Cambridge House Public Assistance Institute in Somerset.

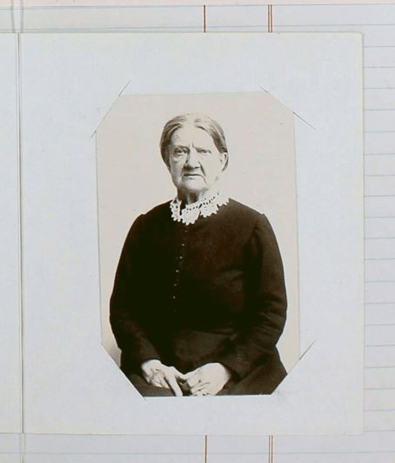

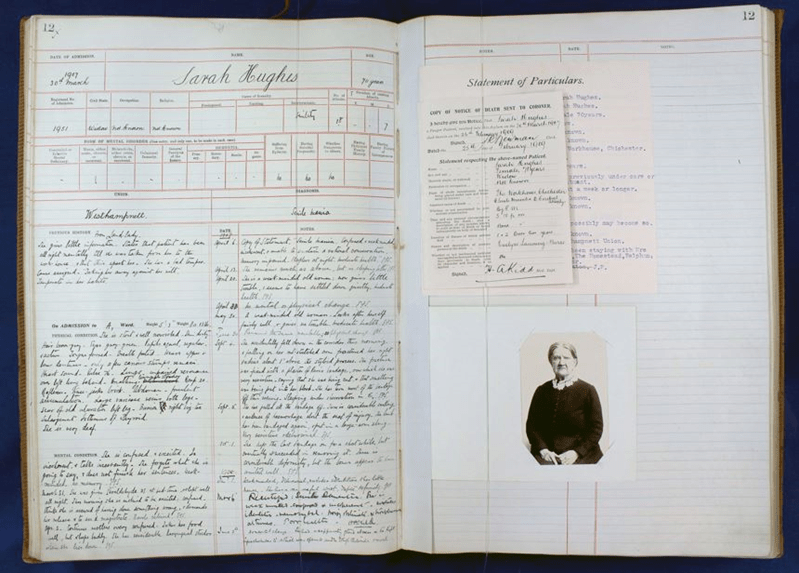

But, of course, these forward-thinking concepts were felt most by the patients and are reflected in the extensive series of patient case books dating from 1897 to 1925. One of Graylingwell’s early patients was a woman named Sarah Hughes. Sarah arrived from Chichester workhouse on 30 March 1907 after her behaviour became “strange” and concerning, her landlady complaining that she’d been violent towards her.

Her case book entry notes that she was a widow aged 70. Little else was known about her life at the time of her admission. However, we now know that she was none other than the celebrated artists’ model Fanny Cornforth, mistress and muse of pre-Raphaelite Dante Gabriel Rossetti.

Sarah – who was born Sarah Cox in Steyning in 1835 – died in Graylingwell on 24 February 1909, a little under two years after her admission. The case book gives the primary cause of death as ‘senile dementia’, from which she was suffering, but was more likely due to pneumonia. She is buried in Portfield Cemetery, Chichester.

Graylingwell patient records have been indexed. Names of patients over 100 years old are available to search via our catalogue here.

Military Hospital (1915-1919)

Just as Graylingwell was settling into carrying out its vision, the First World War broke out. The government requisitioned the hospital for military use and the first soldiers from the Western Front began to arrive on 24 March 1915. The existing patients were taken on by surrounding psychiatric hospitals; the few who remained worked on the farm and estate. What followed was four years of surgical and nursing care, but, despite its peacetime purpose as a psychiatric hospital, it did not treat those with war-related mental health conditions.

Gerald Kidd, the youngest child of Mildred and Dr Kidd, recalled the war years in his autobiography:

“father was Colonel in charge and my mother was in charge of the women volunteers… The blind, gassed and limbless soldiers, arriving within a few hours of suffering their injuries in the big battles, made a deep and lasting impression on me…”

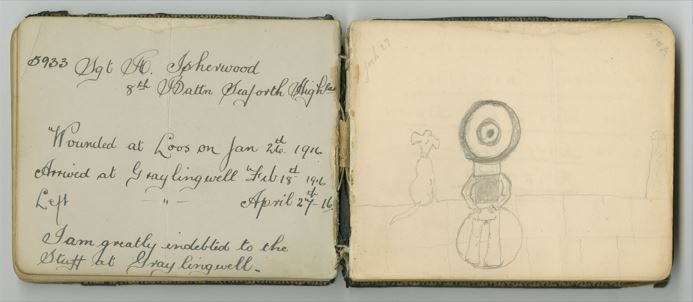

They also left deep impressions on the nursing staff. We hold four autograph books kept by nurses which were written in by the soldiers they cared for. The entries range from words of thanks, quotes, sketches and cartoons, poems, or simply just names and dates.

WSRO does not hold patient records of soldiers from this period. For more on this, please visit The National Archives webpage here.

New Beginnings (1920s-1950s)

After the Hospital re-welcomed psychiatric patients in 1919, it was in a very different world, one which was coping with the trauma of warfare which gave impetus to psychiatric research and care. Dr Kidd oversaw the first few post-war years, but, after retiring in 1926, Dr Cyrus Ainsworth took over as Medical Superintendent.

Throughout the 1920s it became apparent that the Hospital needed to expand; architectural drawings from 1930 show the designs for Summersdale (new admissions block), Pinewood (nurse’s block), and Richmond (chronic and infirmary block for 115 patients). All were designed by the office of Arthur Blomfield, the original architect. Expansion thus continued into the early 1930s, providing more beds for patients and jobs for nursing staff. However, a familiar situation hit in 1939 as the Second World War broke out, and the newly constructed Summersdale block was taken over as a military hospital. This time, the main hospital was able to continue as normal throughout the war.

Summersdale block underwent further changes to its intended use. The 1954 annual report states: ‘On 1st April 1953, Graylingwell, with three other hospitals in this region, commenced an experimental pilot scheme for one year whereby patients who are able to co-operate can receive inpatient treatment without any legal formality’. This was a significant, and humane, decision to offer psychiatric treatment without the need for intervention under the Lunacy Act.[3]

[3] https://www.rcpsych.ac.uk/news-and-features/blogs/detail/history-archives-and-library-blog/2021/01/26/reforming-mental-health-act-history

By the mid-20th century, the hospital was enjoying a good reputation and was considered among the best in the country. Dr Brian Vawdrey was a particularly notable member of staff who employed art therapy to help treat patients (find out more about the Vawdrey Archive Project here). The 1950s also saw the creation of the Medical Research Council unit, and the hospital later made international headlines when it pioneered out-patient treatment with ‘The Worthing Experiment’.

Following a lengthy period during which patients were moved to other accommodation, the hospital finally closed in 2001.

Hopefully, this blog has offered a potted history of this hospital whose heritage is deep and far reaching. There is much to be learned from the Graylingwell archives, falling outside of the scope of this piece, but we look forward to helping researchers access this collection now that the catalogue is available.

For more on the history of Graylingwell, see Beneath the Water Tower. Copies are available to purchase via our website here.

A note on patient records:

Patient records include admission and discharge registers, patient case books (up to 1925, many with a photograph), and some case files. Please note that access to patient records is restricted for 100 years.

Stay up to date with WSRO – follow us on Facebook, Instagram, Threads, Bluesky and YouTube

My grandfather Herbert dart worked in West Sussex County Asylum, Chichester between 14 July 1904 and 31 March 1908 before moving to the newly built Cardiff City Mental Hospital on 8 April 1908. I was wondering if there were any staff records for that period which might include his details.

Regards

John Hendry

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks for commenting. I have searched our catalogue and have located 2 items from the Graylingwell archive that mention Herbert Dart working there. If you would like to view them in our Searchroom or purchase copies, please email us at record.office@westsussex.gov.uk to find out more. – Vicky

LikeLike