By Abigail Hartley, Searchroom Archivist

I, like many others, watched heartbroken as the roof and spire burned during the recent fire at Notre Dame de Paris. Thankfully, many of the artworks and relics were rescued, no visitors were harmed, and the facades and majestic bell towers are structurally stable. I took this as a sign of how good medieval engineering can be (though we will get to when they were clearly just making it up as they went along). I was also told that all of the 180,000 bees that apparently live in the roof of the Cathedral also survived, albeit quite ‘drunk’ from the smoke. This fact led to a sigh of relief for the poor things followed by a sudden befuddled realisation that apparently there are genuine live actual bees living in the roof of Notre Dame.

All glib remarks aside, the image that will stick with me is seeing on twitter, as it happened, the collapse of the spire. It was not the oldest part of the Cathedral, indeed it was part of the renovations during the 19th century, but it was deliberately designed to invoke the late medieval Gothic stylings of the 800 year old building. It showed how good the Victorians were at incorporating then modern materials, tools and designs into much older foundations, and how even their efforts could not stop the extensive damage from occurring.

Regardless, this inevitably led to thinking of much closer to home. Many comparisons have been drawn to York Minster, which has suffered horrendous fires in 1829, 1840 and most famously 1984 after a lightning strike. Lesser known by the general public but closer still is Chichester Cathedral, whose own spire collapsed in 1861. It is estimated to have cost somewhere between fifty and sixty thousand pounds to rebuild, and it remains the spire that you can see (under a substantial amount of scaffolding around its base) to this day.

Chichester Cathedral has the reputation of being (and I say this with the greatest affection possible) pretty standard as far as Cathedrals go. The greatest things of note remain that it is the only Cathedral visible from the sea and it has a separate bell tower. Otherwise the construction has been altered very little over the years in comparison to its cousins in Lincoln or Gloucester. Part of the reason for this, and part of the reason for the dramatic tumbling of the spire in 1861, is the problem of subsidence. In other words, it is slowly sinking into the ground. This is due to the foundations upon which it was built being unable to support its weight. A visible consequence of this is the bell tower. Have you ever wondered why it is separate to the main structure? It is simply too heavy to be included safely in the Cathedral proper.

As a consequence, various parts of the building have caved in at one point or another, with the South West tower collapsing in 1210, the North West in 1635, and of course, the ‘original’ spire in 1861, which had been partially restored in the 1600s by Christopher Wren. Of course, to say that it was the ‘original’ spire is a bit too simple. It was built in the 14th Century, around 200 years after the Cathedral had first been consecrated in 1108. Some spires that we see today on our Cathedrals are later editions built on foundations that were most definitely not designed with the knowledge that someday someone would get the bright idea to put severe structural pressures on its walls. Beautiful? Yes. Structurally sound? Mmmmmm… This author is no architect but even she suspects that Gothic additions to Norman structures were often poorly thought out and executed.

Chichester Cathedral is not atypical of English Cathedrals in its architectural mishaps. Hereford’s western front has collapsed in the past, and many spires across the country have fallen at one point or another, usually during the construction stage in the eleven through fourteen hundreds. Winchester, Ely, Gloucester, Lincoln… and indeed Chichester have all had parts fall off at one point or another, sometimes multiple times over their existence.

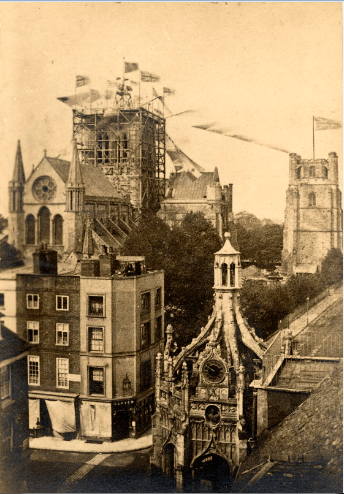

And so I got to thinking about what we held at the record office. My colleagues had made a post here and there about the collapse of the spire, and a quick search brings

up a series of photographs showing the aftermath of the disaster shows how extensive the damage was. What follows is all information obtained from sources held at the West Sussex Record Office.

Half past one in the afternoon on the 21 of February 1861 was well documented by eye witnesses and local newspapers, with the Illustrated London News in particular making a series of beautiful (if slightly Romanticised) depictions of the ruined church and the restoration works. George Braithwaite, the sub-Dean, described the event, ending with “…Silence was restored; and the debris rested like some soldier in the grave”. It deeply affected the city, with the Dean himself described as “leaning over his table sobbing, his face buried in his hands”.

Poems were written and committees were held, affirming that restoration work would begin almost immediately. Subscriptions for funding began, with Queen Victoria and Prince Albert giving £350, and the Duke of Richmond giving £1000. £40,000 was the estimated cost, and initially around £20,000 had been received. Much more would be needed to build a new tower.

The five foot cracks that were large enough to fit a man’s arm into were seen as such a drastic level of damage that many felt that it could not have been the result as something as simple as the long decay of time. There had to be a more malicious cause surely? Arguments continued back and forth, some blaming the weak medieval architecture, others blaming the storm the night before, others pointing to bungled restoration work which had begun when the large cracks were discovered. It seems time did the damage, improper precautions and ill-informed consultants led to further structural weakness, finalising with one stormy night being enough to make the damage irreversible and the collapse inevitable.

The spire was rebuilt taller than before, and lead to papers and discussions on how best to preserve ancient buildings, building on what had been started in France, with the publishing of The Hunchback of Notre Dame. Notre Dame de Paris had been left in a state of disrepair before Hugo’s famous novel emphasised that these buildings will outlast and oversee all of the conflicts created by humans if revered and cared for in the right way. The book acted as a sort of wake-up call across France. Indeed it is difficult today to imagine a France were historical preservation does not form a significant aspect of their cultural identity. This impact of Hugo was felt across the channel, with many Cathedrals and Abbeys having work done to their edifices and interiors. The Cathedrals were designed to outlast the people that would pray within them, and later dodgy additions to the main structures meant that greater care was needed when working on these grand buildings. G.G. Scott, the man who would design the new spire, gave a paper on the conservation of ancient buildings in 1862, and would go on to sit at a committee for the conservation of monuments and remains. One decade later SPAB (the Society for the Protection of Ancient Buildings) would be founded by William Morris, which continues to this day.

The planning and rebuilding of the Cathedral spire took five years, with the first stone being laid by the Duke of Richmond in May 1865. By the end of that year the spire was 60 feet high, and on an almost fittingly stormy June 28th 1866, the weather-vane was placed on the spire, crowning it at eight feet higher than it had been previously. Internally, restoration work took a little longer, with the 14 November 1867 marking the first service held with all the work complete.

Moving forward to the here and now, the Cathedral is currently going through further restoration work (the roof. Always the church roof…) that will take several years. It will undoubtedly look beautiful and relatively solid once complete, and, as far as I know, will continue to not have bees (intentionally) living in the new lead roof. We do, however, have peregrine falcons, which you can watch on a livestream here, more impressive than bees for sure?

Stay up to date with WSRO – follow us on Facebook and Twitter

I have included below a full list of references which I consulted when writing this post. This may be of interest to those looking to do more research into the history of the Cathedral. I certainly came across far too much to include in a 1,500 word blog post, but by copying and pasting these references into our online catalogue, you can decide for yourself what records may be worth viewing on a visit to the record office. It’s worth noting the variety of sources these records originate from, showing that the collapse of the spire affected more than just the Cathedral grounds and staff, it went beyond even Chichester and Sussex. It also does not include the dozens of photographs and prints taken of the Cathedral, before and after the incident. That I’m afraid, is a task I leave to any potential researchers.

- Wiston Mss 7077

- Wilberforce Mss 62

- Shippams 1/8/4/12

- Par 86/7/14

- Par 44/1/5/2

- Par 41/8/2

- Par 37/12/1

- MP 378

- MP 192

- MP 130

- Lib 15818

- Lib 14402

- Lib 5105

- Lib 5099

- Lib 204

- F/PD 275

- F/PD 266

- F/PD 164-169

- Fuller Lib 35

- E/35/12/1

- Cutten Mss D/2/7-12

- Add Mss 22523

- Add Mss 1010

One thought on “Bees, Falcons, Gothic Alterations and Collapsing Cathedrals – the Story of Chichester’s Fallen Spire”