By Alice Millard, Research Assistant

Puglism, n. The art, sport, or practice of fighting with fists; boxing.

In the few years that I have been working at West Sussex Record Office, I have stumbled across several 19th century documents relating to pugilistic pursuits in the county. I had wrongly assumed prize fights were the domain of cities like London or Birmingham. In fact, the seclusion of more rural counties offered some protection from the law; pugilism (and the gambling it encouraged) occupied a hazy space in terms of how ‘permitted’ it was; whilst this incredibly dangerous sport was, technically, outlawed, authorities often turned a blind eye. This blog will take a look at some of the celebrity matches which took place in West Sussex, and the documents which record them.

Dutch Sam vs Tom Belcher, Crawley 1807

An article in the Stamford Mercury (28 August 1807), reported on a “renewed battle between Young Belcher [Tom Belcher] and Dutch Sam* [Samuel Elias]”. Theirs was a long standing feud between two highly skilled pugilists of their time. Just a few weeks prior to this match, Elias and Belcher had fought 34 rounds at Moulsey Hurst in Surrey. Those present to see Elias declared the victor included the Duke of Clarence, amongst enough members of the nobility to account for “about 1/5th of the Court Calendar”, according to the Ipswich Journal (1 August 1807).

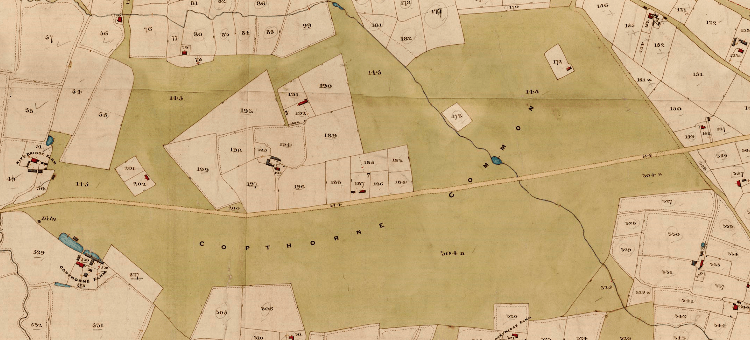

After Elias’s initial victory, the pair then met again on Lowfield Common on 27 August 1807; presumably just a few minutes away from the village Lowfield Heath which was located to the north of Crawley – the area now around Gatwick Airport. The match took a gruelling 36 rounds lasting 33 minutes to conclude that Elias was again the winner.

*Dutch Sam was not, in fact, from the Netherlands. He was born in Whitechapel to a Jewish family who had, at some point, emigrated from Netherlands.

The Public Ledger and Daily Advertiser (21 August 1807) reported that towards the end of the match “Sam could only be compared to ferocious bull-dog attacking his prey”. In a terrible state, Tom Belcher was taken by his brother Jem (also an infamous boxer) into a “gentleman’s chariot” and whisked away. It was reported that Elias’s “only material injury was a severe blow under the eye”. It seems he got off lightly.

Tom Cribb vs Tom Molineux, Copthorne 1810

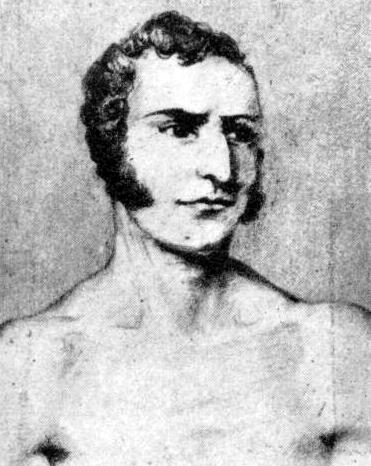

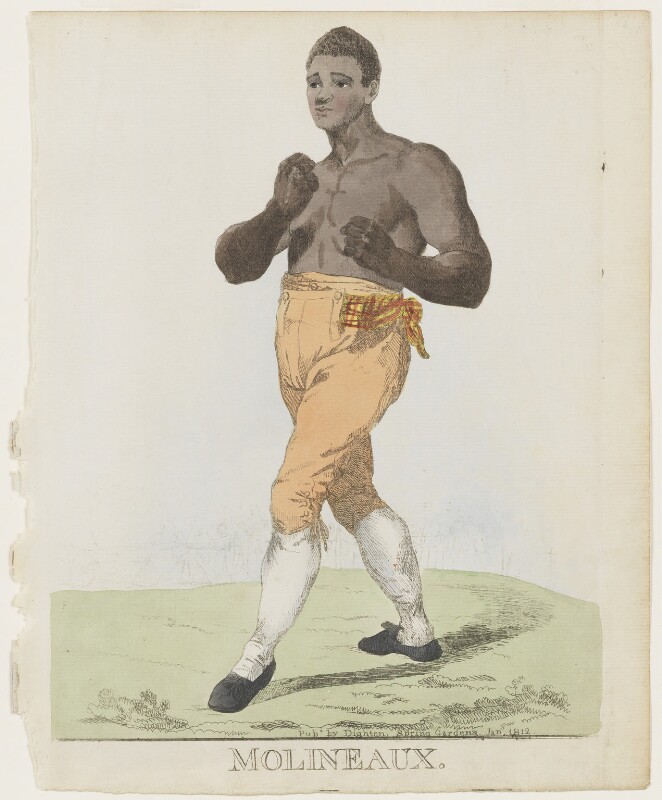

Another notable boxing duo held a boxing match on Copthorne Common on 18th December 1810. Tom Molineux was an extremely popular boxer from America. He was born in Virginia but little is known of his background. Some have suggested that he had been born into slavery on a plantation but others have discredited this. Molineux’s trainer was another American man called Bill Richmond; a highly-skilled pugilist who had been born on a plantation owned by enslaver Rev. Richard Charlton.

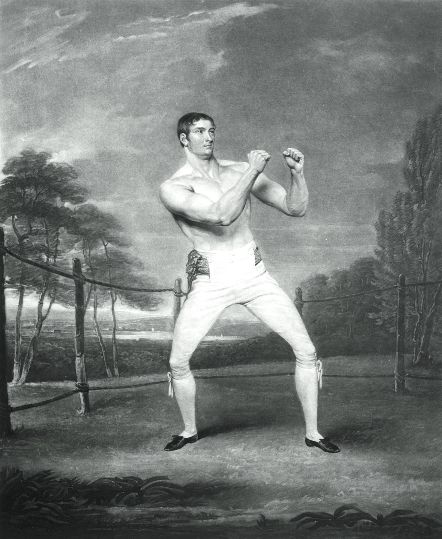

Tom Cribb was a Bristolian, but had moved to London by the age of 13 and worked as a bell hanger and coal porter. The art collection at Petworth House includes a large sculpture of a ‘British Pugilist‘, which some have suggested was modelled after Cribb.

The Hampshire Chronicle (24 December 1810) reported that the bets were 3 to 1 on Tom Cribb. Present at the fight on Copthorne Common – at 12pm – were near 10,000 spectators who “got a complete soaking by a heavy rain”. Cribb and Molineux sparred for an excruciating 55 minutes during which both had lost their ability to see, such was the bruising and swelling to their faces.

The London Courier and Evening Gazette (24 December 1810) reported that Molineux was particularly on form, though noting that “there was shown [by the audience] a little national prejudice against the Black [Molineux]” – presumably a euphemistic explanation of abuse geared towards Molineux’s ethnicity. Despite the pressure he was under from Molineux, Cribb went on to win after 33 rounds by which point both men were completely exhausted.

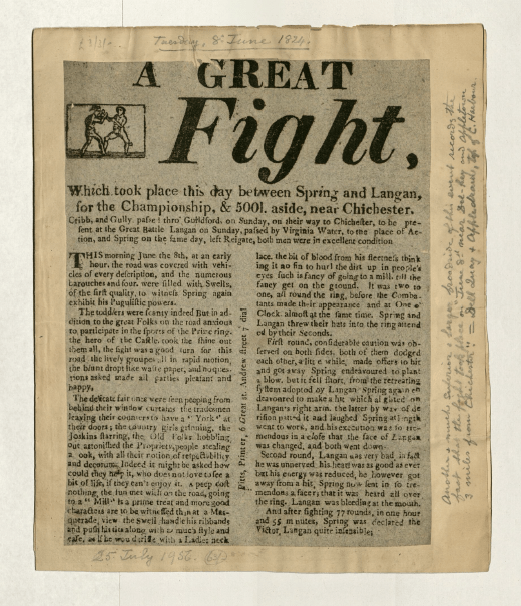

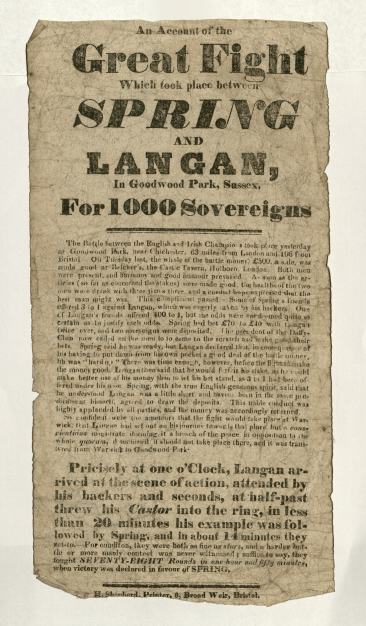

Tom Spring and John ‘Jack’ Langan, Birdham 1824

Tom Spring was the heavyweight champion of England between 1821 and 1824. Spring had previously fought Irishman John Langan in Worcester in January 1824, but the fight had been marred by rioting. Despite Spring winning their previous fight in Worcester, he agreed to Langan’s request for a second match, so that they could both restore their reputations. Spring was known for his defensive moves, rather than his power. On the other hand, Langan was particularly brutal.

“His [Langan’s] first recorded bare-knuckle fight took place when he was just 13… At 17 he was accused of murder when he ‘killed’ a 26-year-old called Savage in an all-day fight. Savage, however, rose from his coma and lived to be 93.”

The second fight was fixed for Tuesday 8th June and Birdham was selected as the location just days prior to the event. The prize money was also set at £500, around £38,000 in today’s money, and was a small fortune when you consider the average annual wage of a labourer was around £16.00. The night before the fight, Spring and Langan travelled to Chichester; Spring stayed the night at the Dolphin Hotel in West Street, whilst Langan stayed at the Swan Inn in East Street.

It was estimated that a huge crowd of 40,000 spectators came to the match.

“Fifty-three large wagons were arranged in a circle round the field for spectators (five shillings a seat) and a grandstand from Epsom Racecourse was erected at one side (one guinea a seat). The ring was 24 feet square and stood six feet above the ground so people could see and also to prevent spectators from entering as they had at Worcester.” – Boxing Champion’s Last Fight

The fight lasted a gruelling one hour and 55 minutes. During this time, Spring and Langan fought a whopping 77 rounds filled with high intensity boxing. Ultimately, Spring was victorious for a second time, but retired the very same year, fearing for his health.

Rev. Peachey and Lord Egremont, 1828

With thanks to Lord and Lady Egremont of Petworth House.

“I believe that there is no better school for good temper and good feeling than the Boxing school”

In the archive of the Petworth House estate there is a set of three letters between the Reverend John Peachey and George Wyndham, the 3rd Earl of Egremont. In these letters, Rev. Peachey expresses his concern about an upcoming boxing match in his parish, and his dismay at the lack of action by Wyndham as a local Justice of the Peace. Peachey most decidedly viewed the sport as a morally dangerous one and he desperately wished for the Earl to support his views. However, the Earl’s reply did not alleviate Peachey’s concerns, and I imagine it may have even validated them more.

He said,

“but I do not believe that there is any thing unchristian in boxing no more than in wrestling or cricket, or any other contention of strength & dexterity, & I believe that this prejudice against boxing arises from a comparison of terms, for although Boys & Blackguards in any fight with their fists, and are therefore guilty of an unchristian feeling, yet these men who try their strength in good humour, box, but do not fight, because they have no hostile or unchristian feeling… and I believe that there is no better school for good temper and good feeling than the Boxing school”

– George Wyndham to Reverend John Peachey, 1828.

Charles Clarence ‘Clary’ St Clair and Kate Corfield

WSRO holds a collection of records of the Corfield family. It spans several generations, including documents relating to a woman called Kate Corfield, whose name was – for a time – synonymous with that of a pugilist celebrity.

In 1907, news of divorce proceedings between Kate Corfield and her first husband Charles Marshall hit the national newspapers. Kate came from a very well respected family, and Marshall was working as a clerk in Yokohama, Japan. The couple had married in 1899 in Hong Kong. However, the marriage broke down within the year, which must have left both parties reeling.

Kate’s brother, Edward Carruthers Corfield, lived in Rustington in a house called Broadmark Place from which he assembled a vast amount of records on the Corfield family, including those which documented this turbulent time in Kate’s life. These records show that the reason for their divorce came in the form of Charles Clarence ‘Clary’ St Clair, whom Kate had embarked upon an affair with not long after her marriage broke down.

St Clair was an American bare-knuckle boxer, born in New York c1877. In a letter to Charlotte Corfield, Kate’s mother, he claimed to be ‘Middle Weight Champion of the world’. Kate and St Clair claimed they had been married in Hong Kong, although no proof of this marriage was ever produced. The couple travelled to England and settled in Whitstable in Kent for a short time, but had moved to New York by 1906 where St Clair found work as a taxi driver. However, their relationship soon unravelled and had separated within a few years of their arrival in New York.

Stay up to date with WSRO – follow us on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter

Excellent article. I’ve noticed the statue of the pugilist at Petworth and actually asked one of the guides if it was Cribb – the answer given was ‘don’t know’. What a shame we can’t be sure of who modelled for it.

LikeLike