By Imogen Russell, Archives Assistant

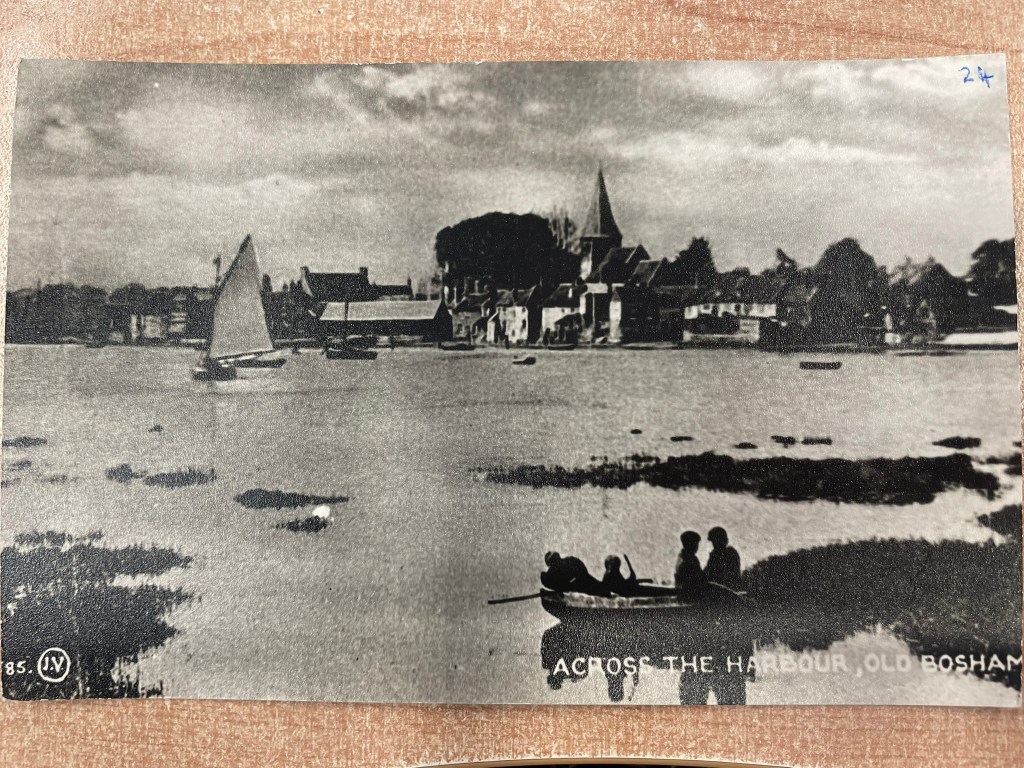

PH 30099, 30084, 30138,30103 & 30085

Every few years or so, we get an enquiry about the “Men of Bosham”. It has always intrigued me and I’ve wondered why it is so important to the history of Bosham and Chichester.

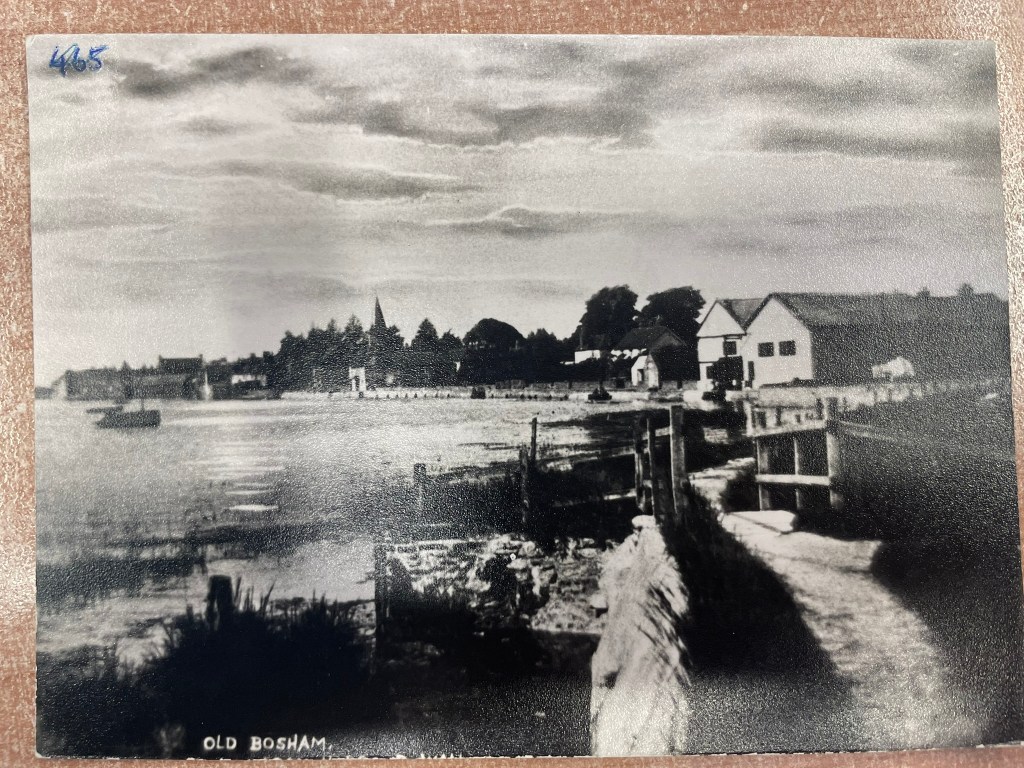

According to several sources, including Maurice Hall’s book on the Medieval Manor of Bosham (WSRO Lib 9338), by ancient custom the Men of Bosham were afforded certain privileges, as tenants of the Royal Manor (Ancient Demesne) of Bosham, including the non-payment of tolls and mooring fees. This custom has, since the Domesday Survey, passed through the generations from father to son.

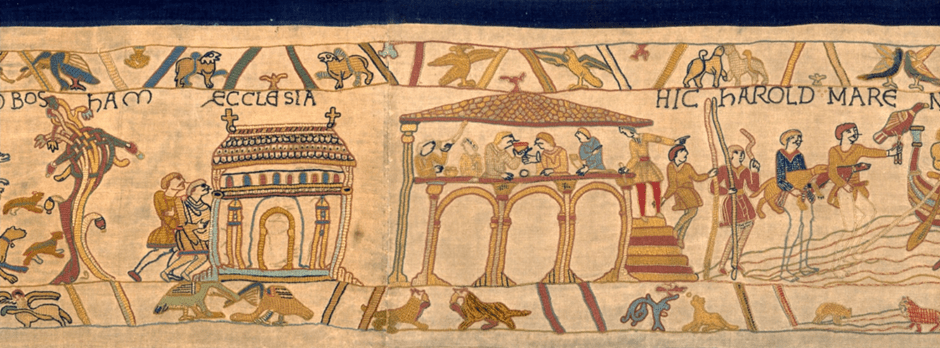

Following the Battle of Hastings in 1066, William the Conqueror acquired all the lands of his predecessor and rival, King Harold, including that of Bosham. By the time of the Domesday Book in 1086, Bosham and other lands in the country had been recorded as manors – rural estates headed by a lord of the manor, populated by tenants working on the land and recorded in the court books as they acquired or “surrendered” tenancies. This is where the terms copyhold and freehold come from. It was called copyhold because the tenancy was recorded in a manorial court roll, and a copy was given to the tenant.

Interestingly, the Domesday Survey records two manors in Bosham, one belonging to the church (Bishop of Exeter) and the other to the King. And it is these two manors that became part of the argument for a court case in the 1960s, where the Lord of the Manor sued a Man of Bosham.

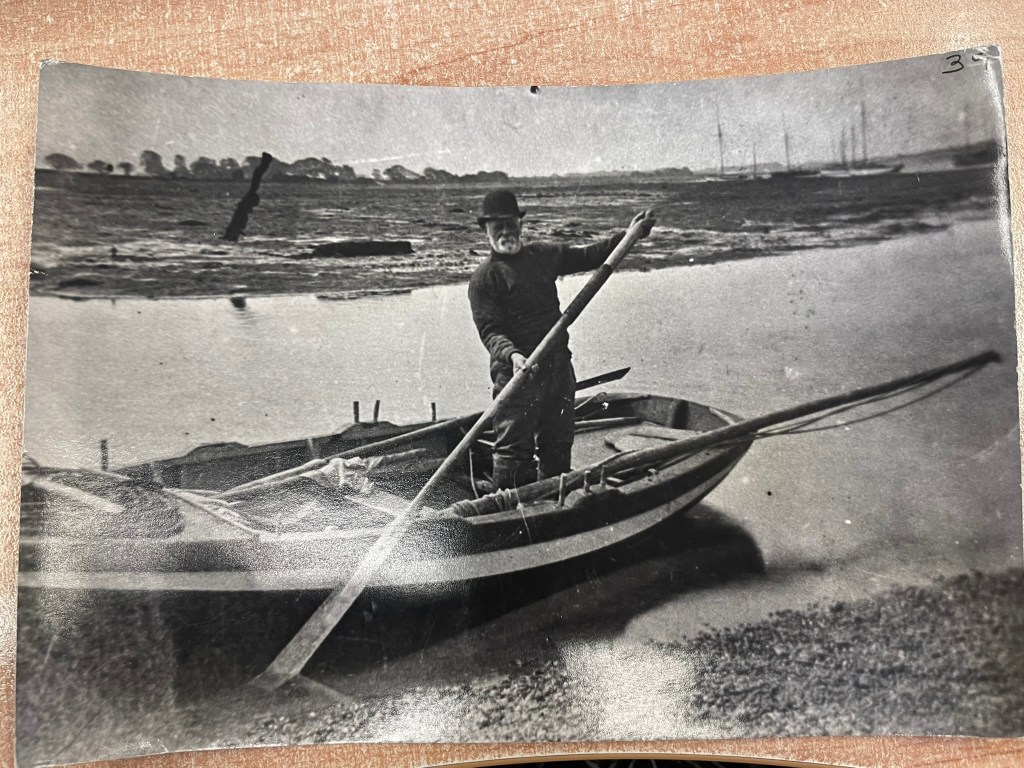

As mentioned previously, tenants living in the Royal Manor of Bosham at this time would have been afforded certain privileges, presumably based on the idea that they were supplying provisions for the King’s Household from the King’s land or sea and, because the Men of Bosham supplied fish to the King, they avoided the payment of tolls.

One story that seems to tie in with the Men of Bosham and supports the “no toll” right is when plague hit the city of Chichester. With the city cut off and nothing or no-one coming or going, the fishermen of Bosham rallied round and left a supply of food outside the gates. Payment of coins were left in buckets of water to sterilise them and as a note of thanks the Men of Bosham were permitted to sell their goods free from payment and a hawker’s licence. It is unclear if this story relates to the plague in 1665 or the Black Death in 1348 but, nevertheless, supports the non-payment privilege.

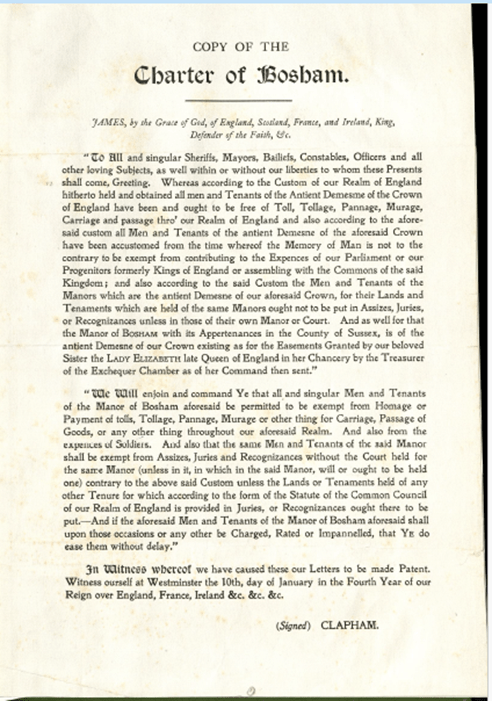

Regardless of this story, several amendments and confirmations were made, over the centuries, by different monarchs as to these rights, including Richard I in 1189, Richard II in 1388, Elizabeth I in 1568, and finally by James I in 1606/7. The amendment of James I is the last known charter signed and sealed by a monarch that we have and is the one of most interest. It is one of the few surviving documents where the rights of the Men of Bosham are officially stated and says:

“ That all and singular men and tenants of the Manor of Bosham… be permitted to be exempt from homage or payment of tolls, tollage, pannage, murage or … for carriage, passage of goods or any other thing throughout the aforesaid Realm. And, from the expenses of Soldiers… exempt from Assizes, Juries and Recognisances without the court held for the same Manor…”

The Men Today

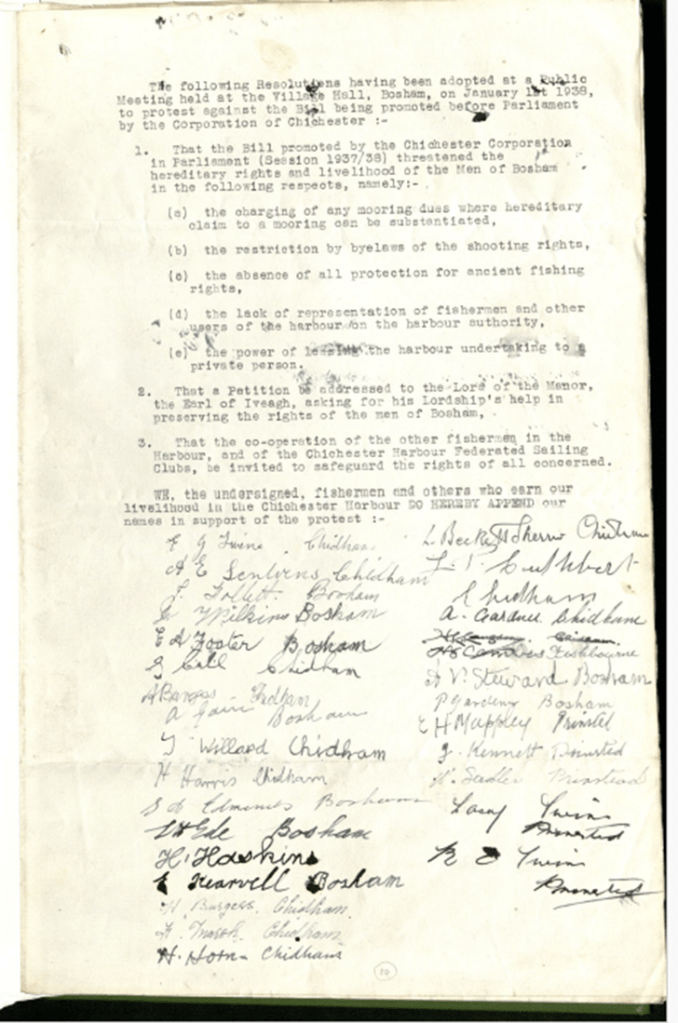

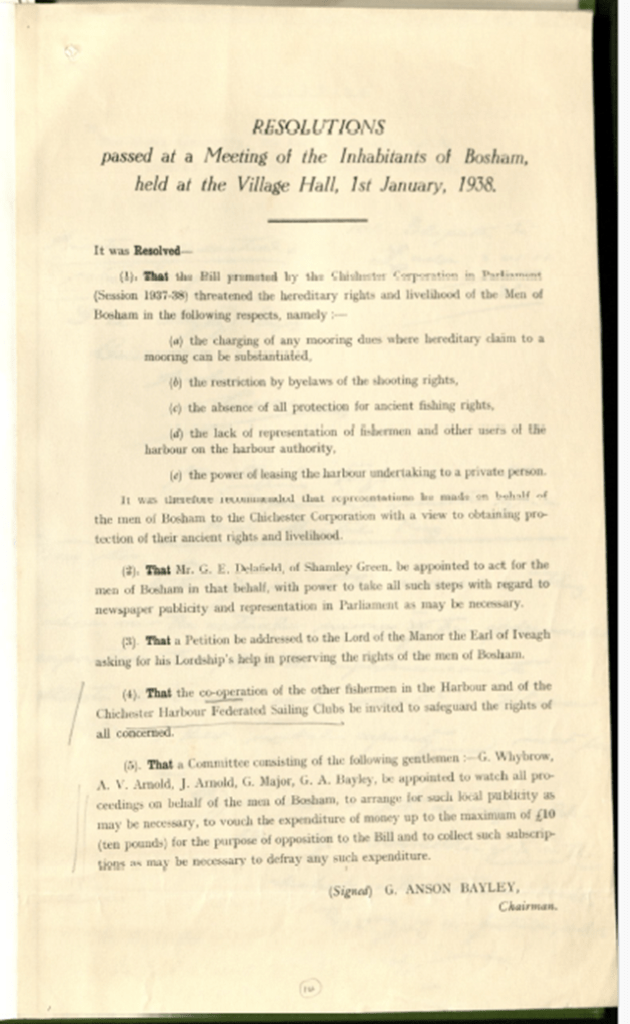

The 20th century set about changes to the rights of the Men of Bosham. The first came in 1938 with The Chichester Corporation Bill and then in 1960 with a case heard in the High Court between the 2nd Earl of Iveagh and Mr E C Martin.

The Corporation Bill of 1938 sought to extend the powers of the mayor, aldermen, and citizens of Chichester regarding Chichester Harbour, but in its initial stage did not consider the hereditary rights of the Men of Bosham, in particular the fishermen. Several fishermen took up the cause to keep those rights and in May 1938 the rights of the Men of Bosham were officially sanctioned and named the Men of Bosham “Statutory Men of Bosham”. In 1951, there was recorded a total of 42 men from 12 families. You can read more about the fishermen’s petition in the correspondence set out in Add Mss 2971. And you can view applications for the various men in the Harbour Conservancy collection (HC/10/1).

The Bill in 1938 set out a modern-day definition stating that a Man of Bosham is one who supplies the Chichester Harbour Conservancy with a certificate signed by two Justices of the Peace (nominated by the Clerk of the Quarter Sessions), was born in Bosham prior to 1937 and earns his living fishing, yachting or boating in the Harbour or is a lineal descendant who earns his living in the same way. Incorporating the James I Charter, it also sets out their rights as:

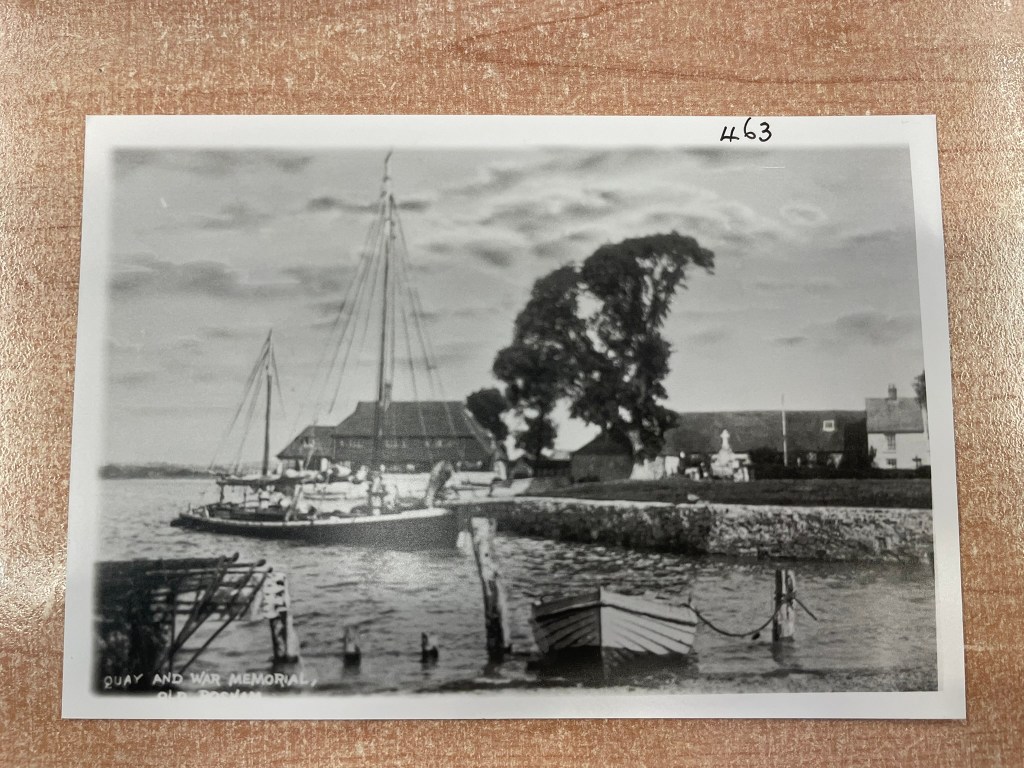

“The right permanently to Moor a boat owned by himself and used primarily for the purpose of fishing on the Foreshore free of charge; to use the Quay without payment for the purpose of fishing and only for embarking and disembarking and unloading of Fish. He further has the right to keep such boat moored at the quay for short periods but no longer than two consecutive Tides. It further states that the men “have the right to use firearms for the purpose of Shooting Ducks or Wild Fowl”.

Correspondence in our Harbour Conservancy collection limits the mooring to the Bosham Channel, but newspaper reports published in May 1960 seem to imply this related to all foreshores in the British Isles.

Iveagh vs Martin

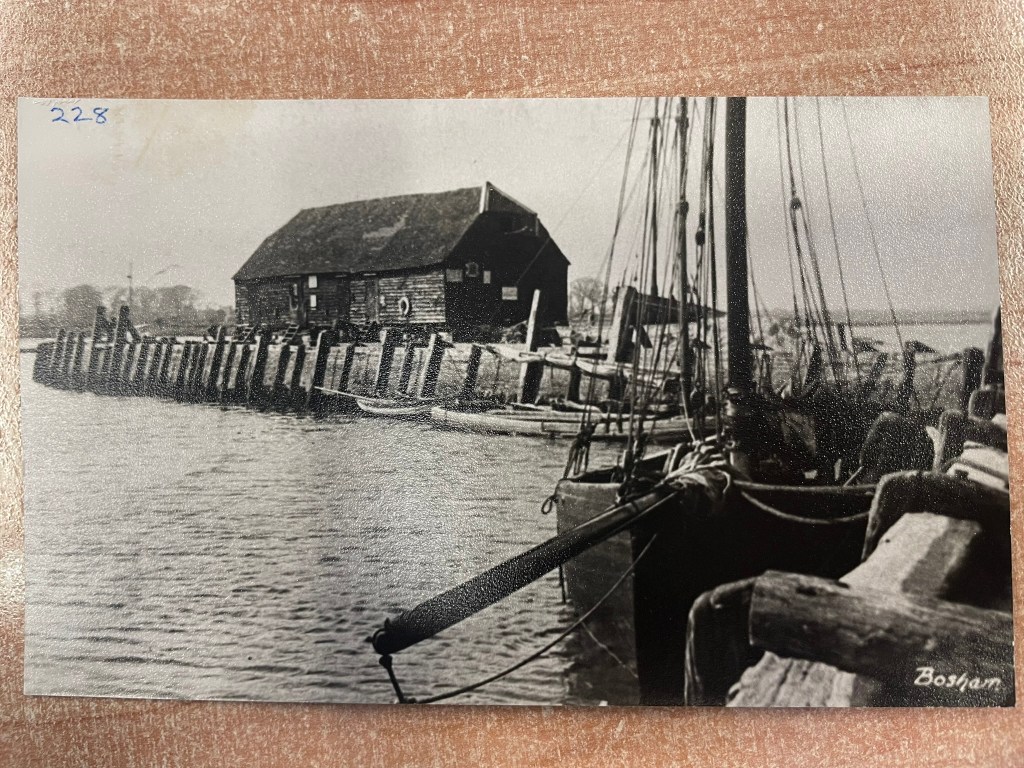

A case fought on principle and heard by Mr Justice Paull in May 1960 at the Queen’s Bench Division of the High Court concerned the payment of mooring fees (£48 19s or £1,026.04 in 2017 money) owed by Mr E C Martin (a Man of Bosham) to the Lord of the Manor (Lord Iveagh). Included in the court case was a petition for an injunction against using the quay without permission, which was quelled by the judge. The case lasted eight days and favoured Lord Iveagh’s claim, receiving half the costs against the defendant.

Newspaper reports of the time (MP 829) report the plaintiff’s argument that while Martin was a Man of Bosham during the case, the fees owed to Lord Iveagh was for mooring his boat at Bosham Quay, between September 1953 and August 1956, at which time he was living on the boat and thus was not using it to earn his living from fishing, yachting or boating. During this period, Martin was not yet a Man of Bosham and technically not a tenant of the land.

The defence’s claim was that he was a common law and statutory Man of Bosham, having a certain right to free mooring on the quay and hard, where he plied his trade as a marine engineer repairing yachts. He further argued that the quay was a public highway and was therefore entitled to exercise the right of the public by going upon it. The notion that the quay was a highway was dispelled with the argument that a highway only applied if public money was spent on it. Lord Iveagh was the only person to spend money on the quay’s maintenance and no public money was ever spent and therefore not a highway.

It is a complex but interesting piece of local folklore and ancient custom, and worth investigating further. So, feel free to pop into the Record Office and find out more for yourselves about this fascinating story.

Stay up to date with WSRO – follow us on Facebook, Instagram, Threads and YouTube

glamorous! 16Farm life during the month of March, 1951

LikeLike