By Mia Curtis-Mays, Archives Assistant

When the Second World War was declared, the protection of the children in targeted city areas, such as London and Portsmouth, was put into action. My great-uncle was a Portsmouth evacuee. Although not evacuated to West Sussex, my Nan’s recollections of her brother being evacuated inspired me to look more into the evacuee experience. I was particularly interested in how the evacuees were educated and how it may have shaped their perspective of country living.

A Teacher’s Evacuation Experience

In 1939, thousands of children from bomb-threatened cities were bundled onto trains to be escorted to the countryside. In many cases, the teachers at the qualifying schools accompanied the children, helping the evacuated have a sense of familiarity when they arrived in their new locations.

A great example of this in our collections is AM 1104 – an evacuation diary written by an evacuated teacher of Mawbey Road Junior Boys’ School, Old Kent Road, London. The document is a beautifully illustrated diary of his arrival in Sompting and an insight into experiences evacuated children and teachers had in West Sussex. A full digital version of this can be accessed on our public access computers in our Searchroom.

AM 1104/1 – Evacuation Diary, 1939-1940

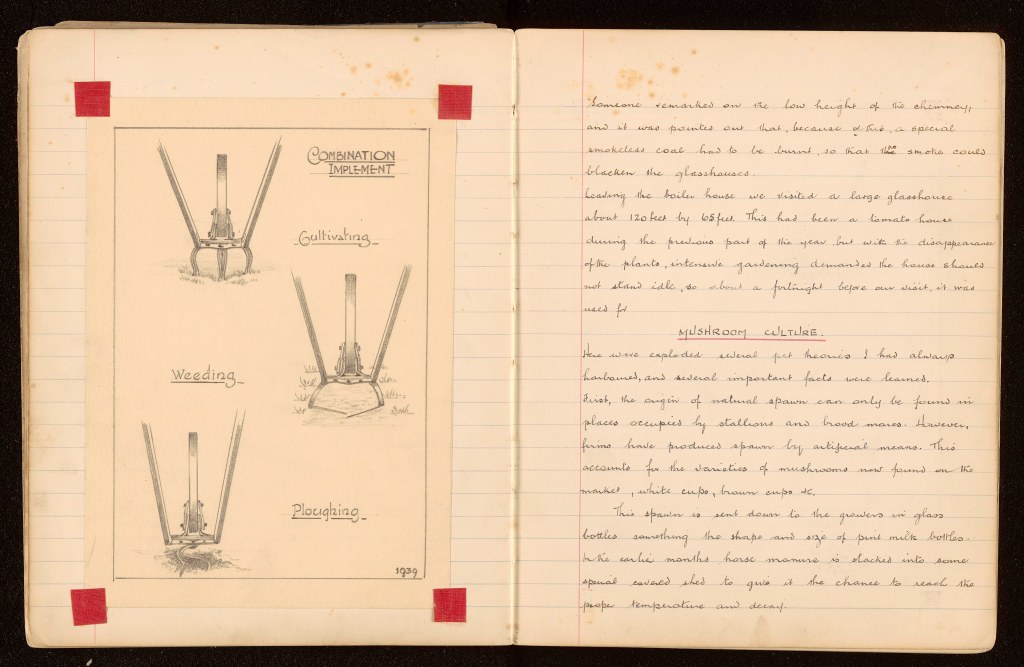

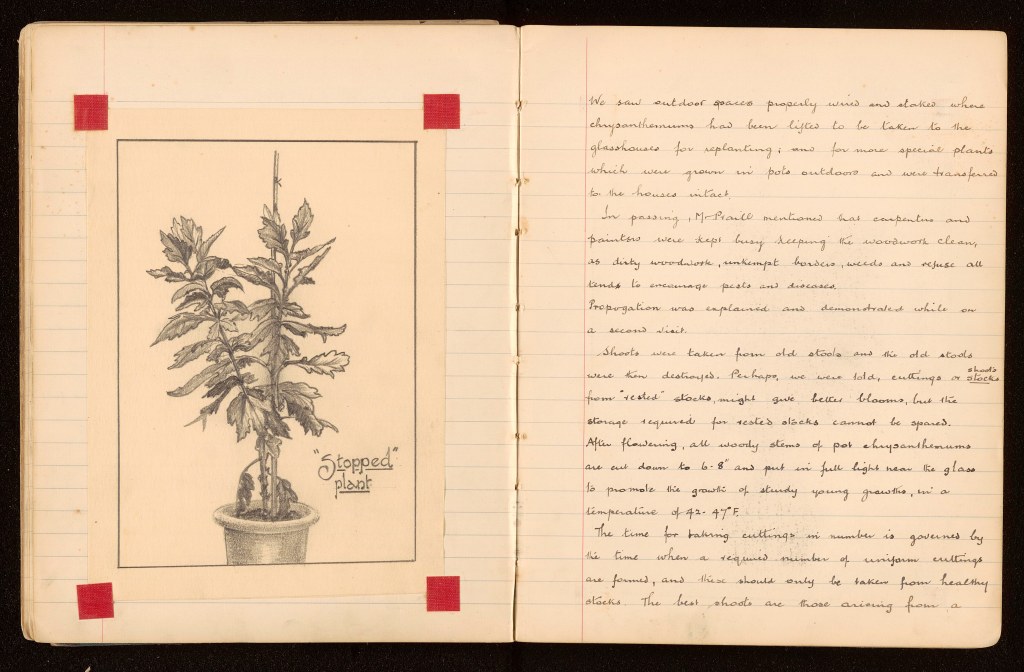

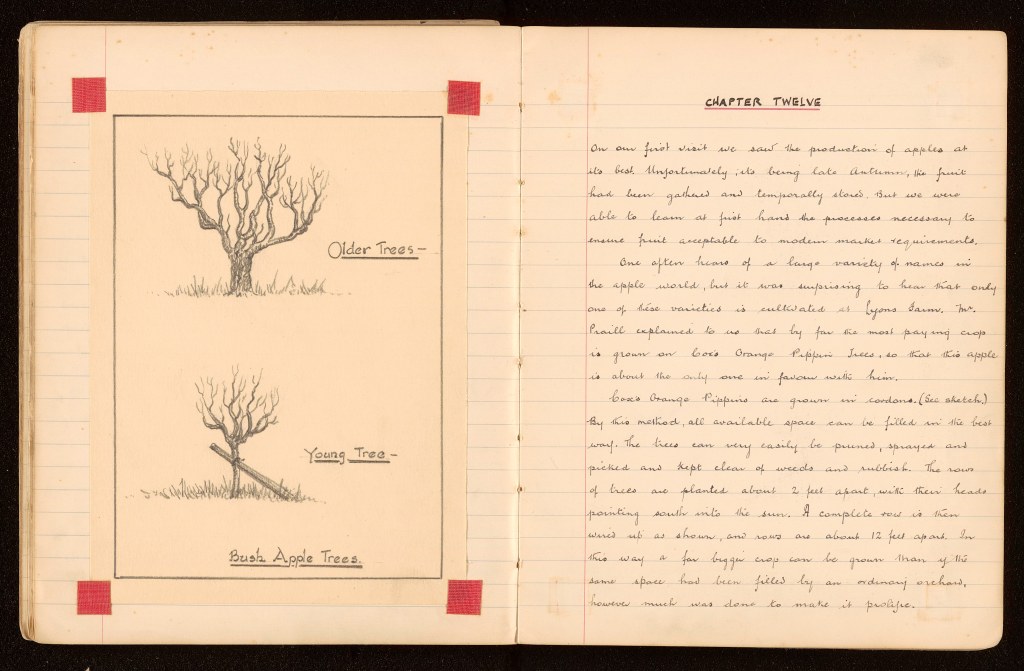

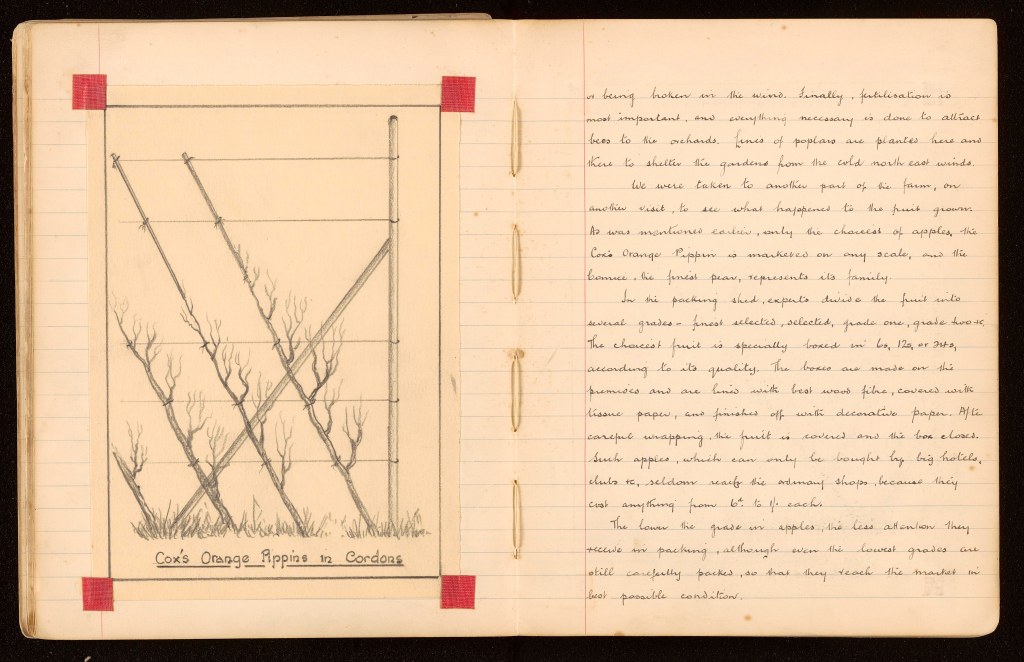

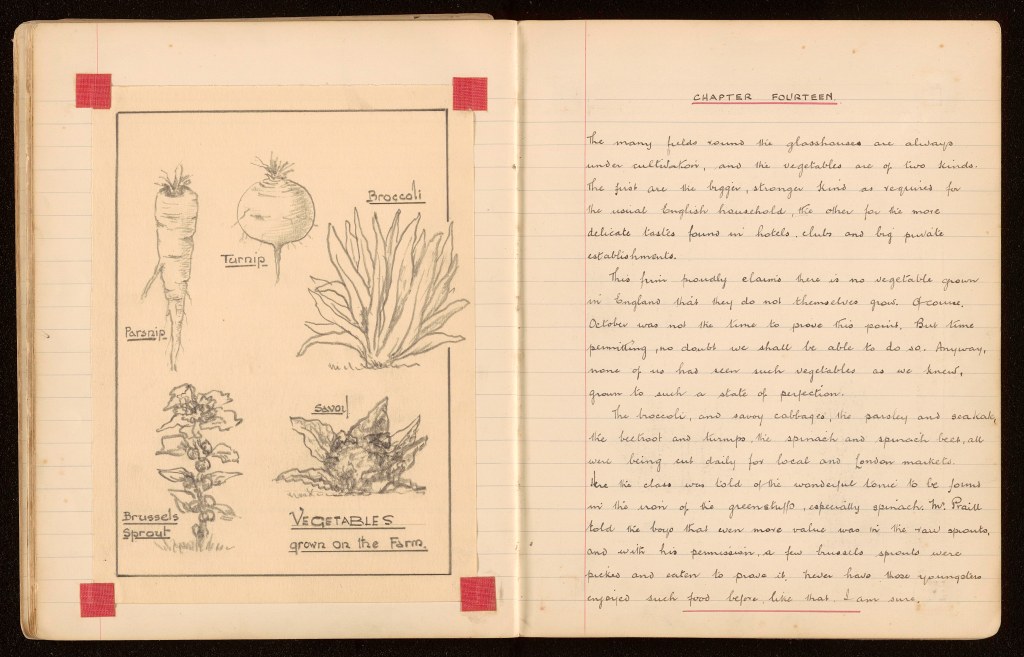

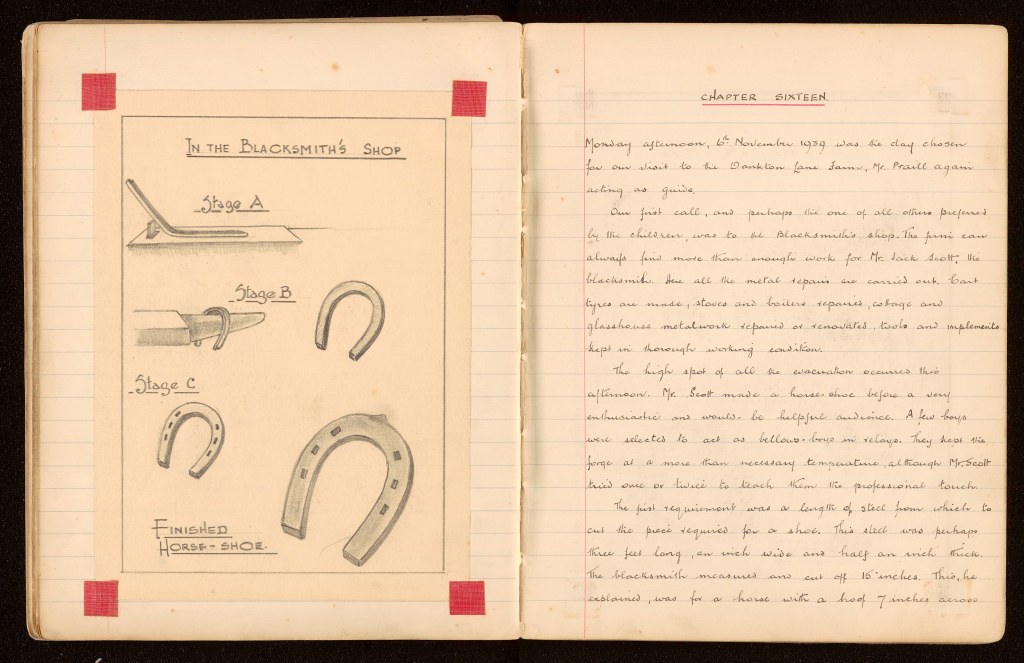

The diary documents the children’s new way of being educated – a more nature-centred approach. They learnt about damages found in hedgerows, the formation of the Downs, studied local weather conditions, and the flora and fauna. Lyon’s Farm was visited to witness how a farm operates, and there is even an entry about the children witnessing a shepherd working his Southdown Sheep. The rural environment allowed the evacuees to experience a completely different way of living and opened their eyes to a world beyond the city.

Unfortunately, like many evacuees stationed in West Sussex, this way of learning was only available when weather permitted. The academic based lessons also took a hit, as availability of space was limited due to both local and evacuated children needing the same educational spaces.

Liaison Officers

West Sussex was advised by the Director of Education to divide itself into 17 districts and to appoint a teacher to act as a “Liaison Officer” for each district. The conference of Liaison Officers was held in County Hall, Chichester. It was agreed that there would be a ratio of one teacher to every ten children, and that this would help the children be less unsettled. Combining teachers and schools did not come without its hiccups; you can read more about the teacher disputes, stock concerns and repayments in WDC/ED16/1.

When reading through the correspondence between West Sussex and the Director of Education, it was clear that in the first evacuation, everyone was more willing to help the children out. However, when it came to the second evacuation scheme, there was more concern. 1,100 children from London (read more about the London evacuees in a previous blog post here) and 2,400 children from Portsmouth and Southsea were due to arrive. Overcrowding of schools was already an issue and resources were depleted. In response to the second evacuation, Liaison Officers asked for more planning and resources to accommodate all these extra children. More about the second evacuation response can be read in WDC/ED16/2.

A New Curriculum

As well as the correspondence between Liaison Officers and the Director of Education, we have many of the circulars concerning evacuation and schooling. These were booklets sent out from the government to give guidance in these wartime situations. The circulars give more insight into how schools were expected to educate children in wartime, particularly evacuees who were now being schooled in a completely different environment.

Like in modern day, supplies can get disrupted due to wars. Schools were told that the supply of material for craft activities were likely to stop. This meant that there would be a shift in the importance of certain subjects. The development of a child’s knowledge of his own language by means of speech, reading, and writing was considered the most essential part of a child’s education, as well as the power of expression of speech. Children were required to also express themselves through music, movement, drama and dancing.

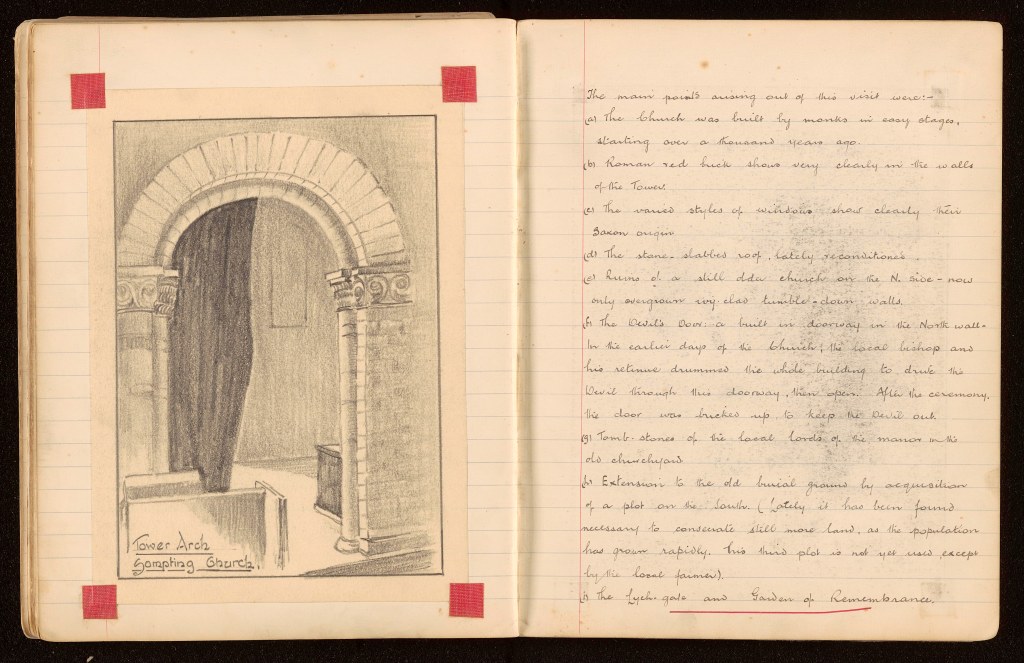

Teachers were permitted to use the countryside as part of their curriculum. The environment would form a basis of the child’s knowledge of history, biology, geography, and geology. Children were taken on rambles, studied nature and were taught to have a closer contact to the countryside.

It was also important that life skills learnt would be beneficial for the community:

- Gardening was not longer a school hobby, but a way of producing food.

- Cooking became a service to the newly formed community.

- Mending and making clothes became skilled services which every child had to contribute to.

- The care of young children separated from their homes became a national service.

Subjects advised by the Board of Education were:

- Study of Manor Houses and churches

- The Life of the Farm

- Local Surveys

- Care of small livestock

- Gardening

These circulars even included recipes and what food was essential for a child’s wellbeing:

- Milk and eggs and other dairy produce

- Vegetables, fruits, salads, especially tomatoes (fresh or trimmed)

- Fats, e.g suet, dripping, bacon, butter, lard or margarine

- Sugar or honey or syrup

- Fish (especially herrings) and meat (especially liver and lean meat) or cheese

- Cereals

You can read these circulars in WDC/ED16/4.

A Better School Life?

It is suggested that in some cases this rural education provided the evacuees with a better quality of education. For many children, this was the first time they had even experienced a library or a museum. Smaller classes provided closer pupil-teacher links and the evacuated teachers took on a more personal role for the students.

Children’s self-resilience was developed by looking after their gardens and livestock, by repairing their own footwear and mending their own clothes. Teachers took their pupils collecting herbs, acorns, chestnuts and wild fruit. They also organised working-parties to farms, helping with the harvest, peas, beet, potatoes, onions, weeding and muck-spreading.

It is certain that an evacuee’s education was one filled with rural splendour. It makes me wonder if their few years in the countryside made any impact in how they lived life once they returned home. Did they grow up to be gardeners or farmers? Or was the countryside life a passing phase?

Further Reading

If you want to find out more about what we hold about the schooling of evacuees, here are some documents in our collection which I found useful:

- AM 1104

- WDC/ED16/1

- WDC/ED16/2

- WDC/ED16/4

- Lib 16368/123

- Add Mss 52,168

- Par 6/54/14

A new research guide has also been shared about the evacuation records we hold and this can be found here.

I also found school log books written during 1939-1945 a great insight into how the schools were dealing with the evacuation scheme. I would also recommend browsing The British Newspaper Archive for local newspaper articles about evacuees- this can be accessed for free on our public access computers in our Searchroom.

Stay up to date with WSRO – follow us on Facebook, Instagram, Threads and YouTube

Very interesting. My mother had a good friend who used to amuse us with her tales of being evacuated to Sussex from where she lived near Waterloo Station in London. I think she ended up at Bexhill (or possibly Seaford). With a child’s mind, she couldn’t understand why she had been evacuated there as she was much nearer the Germans just across the channel than she had been at home! It was the physical closeness rather than the bombs that scared her. They were later moved elsewhere but to somewhere like Swansea which was bombed because of the docks. Eventually she went back to London where she actually felt safer.

LikeLike

Really good Blog and research Guide Mis, well Done.

When reading these I remembered that AM 733/1 – Hotchpot (Worthing Journal), made a comment about a teacher billeting with the author. Might be worth a read if you have a spare moment.

Immie

Imogen Russell|Archives Assistant, West Sussex County Councilhttp://www.westsussex.gov.uk/ | Location: Record Office, County Hall, Chichester, PO19 1RN

Internal: 53632/53633 | External: +44 (0) 1243-753631 |Lync 24587

E-mail: imogen.russell@westsussex.gov.ukimogen.russell@westsussex.gov.uk

LikeLiked by 1 person